Some folks pin excessive weight on the federal government’s influence over our efficiency and load management industries. Even though billions/trillions of dollars are allocated through the “Inflation Reduction Act” and “Bipartisan Infrastructure Law,” those funds are fleeting. What’s more enduring? Rising electricity prices and load-balancing authorities are pushing for more baseload generation and transmission-line construction – things that are always met with stiff resistance by state and local governments and stakeholder groups.

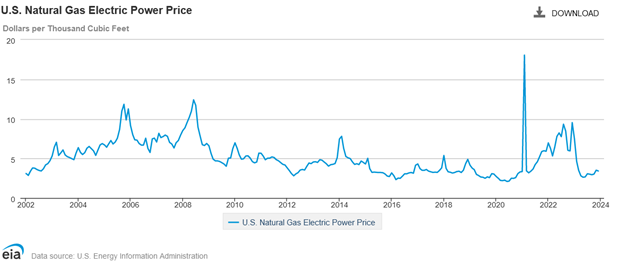

Utility Dive recently reported that electricity prices outpaced the broader U.S. consumer price index. Well, gee, why would this happen? Have fuel prices increased? No. You’d think electricity prices would be set by the marginal cost of electricity, which would be set by the marginal fuel, which is natural gas. While electricity prices shot up, natural gas prices fell precipitously in the last year as modern-day gas production is twice what it was in 2007.

If marginal fuel prices are declining, why is the cost of electricity rising? I would say we are starting to see the rise in the full cost of electricity (FCOE), which I wrote about in TRC is Calling for 1979 and The Deceptive LCOE. In short, the LCOE determines the cost of electricity generated when it’s available. Availability 24/7/365 as we need? That’s somebody else’s problem, and that’s why LCOE is deceptive at best. FCOE factors in 24/7/365 reliability, and when that is incorporated, prices necessarily soar, as I demonstrated in The Climate Apocalypse.

If marginal fuel prices are declining, why is the cost of electricity rising? I would say we are starting to see the rise in the full cost of electricity (FCOE), which I wrote about in TRC is Calling for 1979 and The Deceptive LCOE. In short, the LCOE determines the cost of electricity generated when it’s available. Availability 24/7/365 as we need? That’s somebody else’s problem, and that’s why LCOE is deceptive at best. FCOE factors in 24/7/365 reliability, and when that is incorporated, prices necessarily soar, as I demonstrated in The Climate Apocalypse.

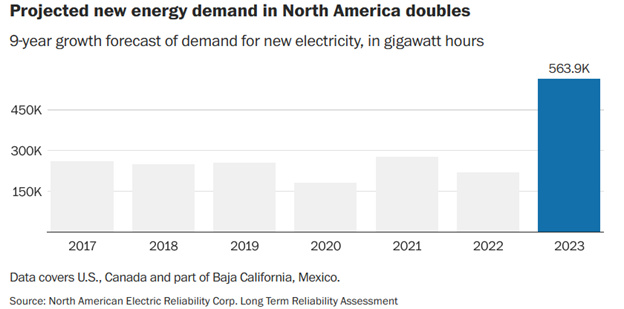

I believe pricing pressure, not anything spilling out of the DC swamp, will propel energy efficiency and load management programs for the next couple of decades and beyond. Suddenly, we have load growth, an insufficient supply of power for manufacturing expansions, and voracious data centers and crypto-mining operations. The Jeff Bezos Amazon Washington Post recently reported that growth projections in Georgia, for example, jumped 17X compared to “what it was only recently. ” The WAPO article featured the following North American growth forecast for electricity delivered to customers.

Here are some additional gems from a Grid Strategies slide deck. In one year (2023 v 2022), the forecast peak load growth for 2028 doubled to 4.7%, an increase in the estimate of 17 gigawatts. A whopping 5.5 GW of the 17 GW are in ERCOT (Texas)! For reference, a utility-scale nuclear power plant, like the Vogtle plants, is a smidgeon more than one gigawatt each. Are there any nukes on the board for Texas? Good luck with that.

Here are some additional gems from a Grid Strategies slide deck. In one year (2023 v 2022), the forecast peak load growth for 2028 doubled to 4.7%, an increase in the estimate of 17 gigawatts. A whopping 5.5 GW of the 17 GW are in ERCOT (Texas)! For reference, a utility-scale nuclear power plant, like the Vogtle plants, is a smidgeon more than one gigawatt each. Are there any nukes on the board for Texas? Good luck with that.

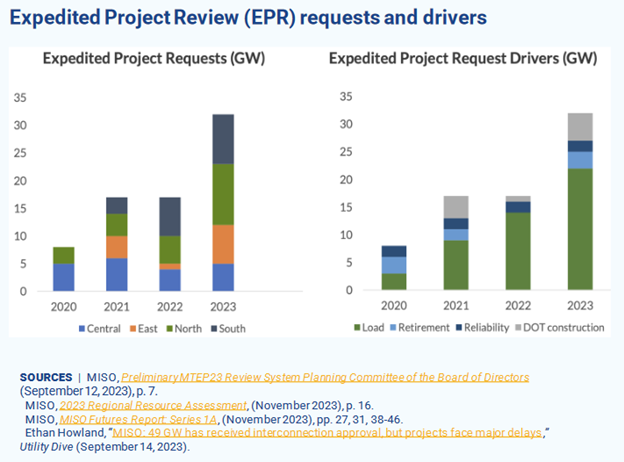

In its current transmission planning cycle, MISO is advancing a potentially record-setting $9.1 billion transmission expansion plan. “One reason for the large expansion plan is the scale of recent Expedited Project Review (EPR) requests. Since 2021, EPR requests have been driven by new load connections. EPR projects driven by new load connections have more than quadrupled since 2020 and almost doubled since last year.” While the WAPO reports “Northern Virginia needs the equivalent of several large nuclear power plants to serve all the new data centers planned and under construction,” Grid Strategies indicates MISO’s data center load is expected to increase 2.86 GW compared to a measly 1.61 GW for PJM (including Northern Virginia).

We are in for interesting times because transmission line permitting and construction averages at least ten years. A typical 365 kV transmission line takes 5-7 years to build, after maybe a decade or more of environmental clearances, permitting, and land and easement purchases to clear the way. All told the timeline from need realization to power transmission is easily 15 years.

We are in for interesting times because transmission line permitting and construction averages at least ten years. A typical 365 kV transmission line takes 5-7 years to build, after maybe a decade or more of environmental clearances, permitting, and land and easement purchases to clear the way. All told the timeline from need realization to power transmission is easily 15 years.

This load growth will exert pressure on utilities and policymakers to deliver, egad, efficiency and load management as alternatives to poles, wires, and power plants. Realistically, efficiency and load management are the only options due to very long approval and construction timelines for supply-side assets. Indeed, efficiency and load management are many years, likely at least a decade or more, faster than conventional supply-side resources to deploy. Will lawmakers and policymakers see demand management and efficiency as resources to keep the lights on? My guess is yes, but like a patient with a growing heart disease risk, only after a blow to the ticker that finds them on their back and waking up in an emergency room. Time to prepare!