This week, we are continuing the discussion from last week’s Pay 4 Performance Sequel post. There is a sequel to the sequel? Last week’s sequel referenced the first attempts at P4P programs, which were delivered around the turn of the century in response to the utility deregulation craze. This post takes us a few steps further.

More Issues to Slay

This post describes why the Energy Service Company (ESCO) model failed and the differences between Energy Service Companies (ESCOs) and modern-day program implementation contractors. Early P4P programs were designed for ESCOs, while today’s are targeted for implementers. The differences pose even greater challenges to the P4P models that failed years ago.

Restrictions

Case studies from the P4P program study, sponsored by the Natural Resources Defense Council, indicate P4P programs in the original waves were overly restrictive regarding measure and project packaging. For instance, one program would not allow bundling of disparate measures – things that have a very high return on investment with things that are more capital intensive with lower ROI.

Energy service companies typically guarantee savings or positive cash flow relative to some baseline to which they and their customer agree. Due to development costs, ESCOs require very large projects, perhaps $1 million minimum, to be cost-effective. The unbundling and cherry picking by customers blows their business model to bits. This handcuffing was a killer for the ESCO business model.

Project Development Cost Risk

Pay 4 Performance programs are fraught with risk for project and program developers and implementers. We covered a couple last week. Another risk is project-development cost. Energy Service Companies offer energy studies “for free.” The “free” part is loaded into their overhead and paid by customers who implement projects. Nevertheless, the objective, of course, is to be as efficient as possible and avoid “dry holes[1],” a term I adore – not! They cannot afford a program to intervene and blow up their project.

Measurement and Verification Risk

As noted last week, early standard offer programs, which pay a flat or prescribed-menu rate per unit of energy saved, were targeted for ESCOs. We can tell how successful this was by measuring how many ESCOs participate in programs today: 0.0. There are a couple reasons for this. First, ESCOs do not appreciate the finer elements of our arcane efficiency program savings estimation and verification methods. The savings equal energy use before intervention, minus energy use after intervention, right? No.

As one of my heroes in our industry said last week at AESP’s Annual Conference, “Programs are designed to be evaluated. They are not designed to be effective.” Whoa – that’s powerful stuff and expect a Rant(s) coming down the line on that thought train.

Second, ESCOs don’t want to hassle with programs and their associated pains, particularly measurement and verification risk. Program M&V will provide a different savings number based on a theoretical baseline. This confuses customers and sews doubt. What business doesn’t appreciate a third party intervening to sew doubt in its ability to deliver?

Business Model Empathy

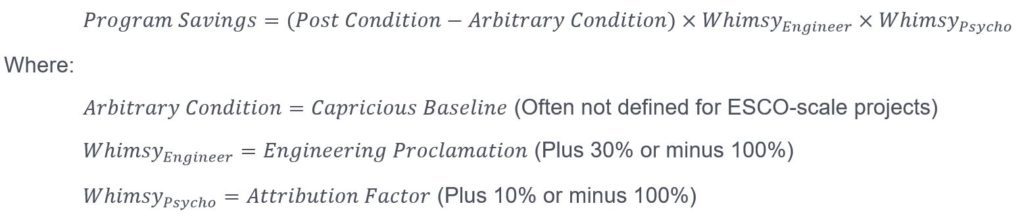

Pay 4 Performance sounds grand. Program implementers do their thing and only get paid for savings achieved relative to a fictitious set of conditions. And in some cases after that filter, it is filtered again, based on another thing my hero said: “whether somebody thinks that guy [customer] would have done that anyway” – that is, attribution. It shifts the double jeopardy risk from the utility to the implementers. For math heads, it looks like this:

ESCOs say, no, thank you.

The implementer business model works like this: we are paid for our time, like attorneys and hairdressers[2]. Unlike ESCOs, attorneys, hairdressers, and implementers aren’t selling anything. We don’t have markups on millions of dollars of capital equipment and installation cost markup. An ESCO can make what they can on the sale of equipment. The standard offer kicker (incentive) is a tiny slice of the profit. The savings, after the double filter (whimsy2) whacks it in half, is ALL implementers get. This is a huge difference and exponentially greater risk for the implementer compared to the ESCO. The implementer can make a tiny bit of money or lose everything. The ESCO simply avoids the program.

The double filter is a tax on savings. When something is taxed, you get less of it. This what my hero was saying regarding program effectiveness.

One more thing to differentiate ESCOs from program implementers; ESCOs can finance their work or easily get lending because they have massive collateral (equipment) for the borrowing. Institutional customers, the ESCO’s bread-and-butter market, are financially sound. It’s low risk. Implementers have no collateral to leverage for getting capital to feed their employees between implementation and the double taxation on savings several years down the road. How can a business pay its employees with no revenue for a year or two? Cash flow problems, anyone?

A Much Better Model

Superior P4P principles are on the way next week.

[1] Term used by regulators and some program administrators as a metaphor for stranded study costs.

[2] Is it ok to say hair dressers?