This year was a blowout for tomato production at the Ihnen household. Enough tomatoes were planted such that if a tomato plague blighted the Ihnen ranch, wiping out 90% of the crop, there would still be plenty for onsite production.

What to do[1]? We visited the People’s Food Coop in La Crosse where we buy nearly all our produce. Cherry tomatoes are selling for $1.80 per pint, and locally grown tomatoes are going for $3.00 per pound. This is great! Clearly, our crop as shown, represents a nice down payment toward an advanced degree for our K-9s.

We loaded all these gems into the Civic and drove to the Coop ready to cash in on the $200-$300 bounty. Ready to make a deal, I was as stunned as the Coop folks were. I demanded retail prices. They scoffed that I was a naïve hillbilly. They have overhead costs, like mortgage payments, utility bills, employees to pay, store maintenance, marketing, insurance, equipment, and furnishings. So what? That’s your problem.

Ok. I can’t take it anymore. You guessed it, and if not, you lose. The fable here is a parallel to renewable energy aficionados demanding full retail prices for net metering and selling their excess site-generated electricity to the utility.

Wisconsin is ground zero for equity (fairness) as the emergence of photovoltaic distributed generation becomes a significant source of grid power. As mentioned in this blog before, the delivery of power – transmission, distribution, and associated maintenance comprises about 50% of a typical power bill, whether the customer is a giant industrial user or a residential customer.

WE Energies and Madison Gas and Electric (MG&E) are seeking approval from the Public Service Commission of Wisconsin to increase their fixed charges to residential customers while at the same time dropping their energy charge rate per kWh. In the MG&E case, the fixed charge, also known as the meter charge, would about double to $19, per the aforementioned noted article. I’m going to take a wild guess and bet that will be revenue neutral. This is known as a “war on renewable energy” – that term captures 17 million hits on google. Apparently lowering the energy charge from 15 cents to 14 cents across the board (for normal customers too) is a war.

The solution for the utility is twofold. First, they need to do a better job of messaging, as usual. Consumers aren’t going to understand that having widespread distributed generation is going to burden non-participants more over the long term. They can understand the tomato allegory described above. How can anyone expect to receive full retail value for a commodity that is produced on the roof of the home, or the garden in front of the home with no delivery charges and infrastructure charges? In fact, it’s a bit like having the mailman pick the tomatoes and deliver them down the street for retail rates – and making someone else pay for the mailman’s extra efforts.

The second piece of the settlement includes a bone for the photovoltaic enthusiasts. To go on a net-metering rate, customers must install a smart meter. The smart meter can be used to charge equitable rates, AND it provides customers with total control over their energy bills.

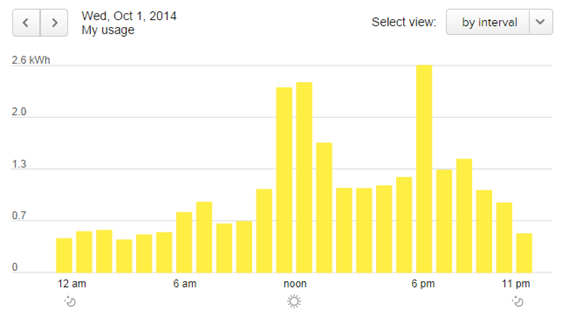

The chart shows interval data for a PG&E customer (a friend from Silicon Valley). Here’s how this solution would work: For the energy sold to the grid, customers receive commodity prices, like a tomato farmer would receive when he delivers tomatoes to a store or a distributor. They would also pay only commodity prices for any energy drawn from the grid. The tomato farmer must pay for delivery and for the service of selling the tomatoes (grocery store). Ok.

In the renewable energy case, the customer would pay for their peak net demand. Net demand equals net draw from the grid: consumption minus production. If a customer is a net positive producer and can supply to the grid at peak times, they are rewarded. In California, as described in this article, the peak demand continues to be about 9:00 PM in the shoulder months of spring and fall. This is when solar panels aren’t doing the non-participants any good.

The bottom line is if consumers want to sell power to the grid, they need a perspective of a tomato farmer. If you do not agree and you think shipping and the grocery store’s markup to cover overhead and profit should be zero, paid by the other shoppers, I’m all ears. If consumers want to sell power to the grid, they need a perspective like that of a merchant power provider. I.e., when energy is produced or consumed is a major factor in pricing. If you can sell delicious August-tasting tomatoes in January, you will get a hefty price. If you can sell power at 9:00 PM in California on March 21, you will receive a hefty price. If the customer helps decrease demand for non-participants, they are rewarded handsomely. If they do nothing to help non-participants – not so much.

It’s that simple, fair, and equitable.