Back in May I wrote that we need to explain the benefits of energy efficiency in simple terms – like our mothers would understand. In that I explained that utilities serve a public benefit, like roads. Since the dawn of energy efficiency, there have been cost effectiveness hurdles – that make little sense to this 20 year veteran, let alone my 80 year old mother. Since this is not (thankfully) my normal area of expertise, it took me a couple hours to figure things out and I’m still not sure I have this all right. That my friends speaks volumes, alone. My head hurts.

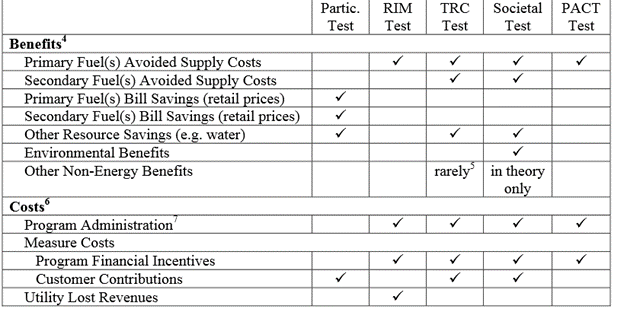

The common tests are super-summarized in the table below from a four year old paper presented at the ACEEE Summer Study for Energy Efficiency in Buildings[1].

Where did these things come from? Why not convert to something a normal person can understand; something that makes sense? A short description of the intent of each of these follows.

Where did these things come from? Why not convert to something a normal person can understand; something that makes sense? A short description of the intent of each of these follows.

Participant Test: This test is for the customer and it is the simplest and most meaningful. Unfortunately, it has absolutely nothing to do with program cost effectiveness.

RIM; Ratepayer Impact Measure: Simply, this is supposed to determine whether custom rates will go up or down as a result of the program. I.e., it is the non-participant test.

TRC; Total Resource Cost: This essentially weighs the value of saved natural resources against all-in energy efficiency costs, including program administration, incentives, and customer out-of-pocket costs for EE.

Societal Test: This test weighs anything you could possibly tie to an energy efficiency measure against the same all-in costs as the TRC.

PACT; Program Administrator Cost Test: This is simply saved primary fuel cost compared to all-in program costs.

Discuss

Energy efficiency is a weird thing to examine from a cost effectiveness perspective, simply because it costs money to get customers to use less energy. In my examples, consider that McDonald’s is energy efficiency and we want to be equitable and fair to McDonald’s.

RIM

The RIM test by its name would seem to make the most sense. I.e, are my rates going to go up or down with the implementation of this program. But look at what is included, primary fuel cost versus all-in program costs and utility lost revenue. However, missing from the table is avoided transmission, distribution and power generating asset costs. This is a bit like determining whether Weight Watchers benefits society, while disallowing the benefits of the dieters and only including the costs of Weight Watchers. The employees are producing nothing. Participants have zero return on investment.

| Cost | Versus | Benefits |

| Program Administration

Incentives Utility Lost Revenue |

Transmission

Distribution Generation Primary Fuel |

TRC

TRC I believe is the most widely used metric for cost effectiveness; hence the title of the ACEEE paper – “Is it time to ditch the TRC”. TRC is similar to RIM but it includes all resources saved as benefits but it also includes customer contributions on the cost side – like we need to add something to the cost side, to arbitrarily make things closer. An example of secondary fuel would be natural gas savings earned in an electric program, from windows, insulation, or temperature controls.

| Cost | Versus | Benefits |

| Program Administration

Incentives Customer Contribution |

Transmission

Distribution Generation All Natural Resources Saved |

In my view, the problem with this test is it includes customer contributions. The ACEEE paper claims with great reason that non-energy benefits are left out of the equation. Another way to view this is – customers buy stuff all the time for secondary and sometimes frivolous reasons. Once again, food is a perfect example. Beans and rice is cheap and nutritious. Why bother with anything else? Uh, taste, time, variety, and even risk avoidance by diversifying the supply. Participants already have their own test. Why arbitrarily throw their cost into this equation?

Societal Test

This test includes the benefits of the TRC, plus environmental benefits, which vary like wind speed and direction depending on the politics of the day, and non-energy benefits, which is like putting a value on the enjoyment people get watching an NFL football game. All I’m saying is these other things are very difficult to price.

| Cost | Versus | Benefits |

| Program Administration

Incentives |

Transmission

Distribution Generation Primary Fuel |

PACT

The PACT is like the RIM test but without utility lost revenue on the cost side. This is obviously a huge difference.

Suggestions

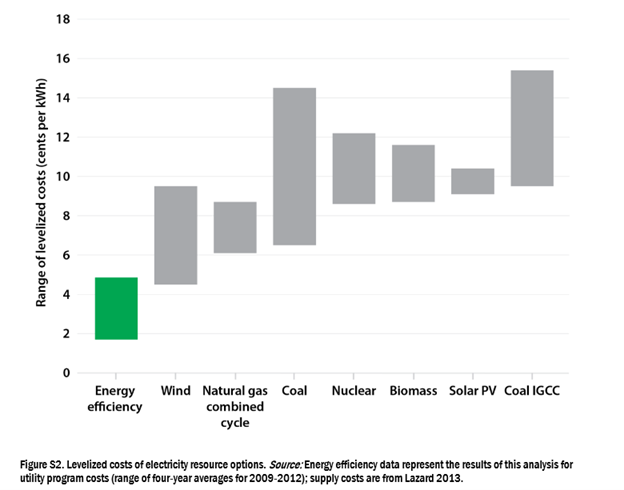

I like to use others’ rantings and ideas whenever possible. In this case, I refer to the ACEEE Summer Study paper linked above. It says the TRC (and all the other suspects) is inconsistent with the treatment of supply alternatives. They use the example of regulators approving purchase agreements for customer-generated energy to sell to the grid (e.g., solar PV, or natural gas generator). No one cares about any of the customer costs, secondary benefits, flavor, convenience, or piece of mind.

Actually, ACEEE already produces a study that compares the cost of energy efficiency to supply resources. The results are shown in the following plot. The cost of energy efficiency shown includes all program costs, incentives, and even what is left and paid by the customer. I would even argue that the customer’s cost should be left out as discussed above. But I’ll even concede all that and include participant cost. As shown, it is least expensive compared to supply alternatives.

[1] I don’t go out to look for this stuff. It accumulates on my “I need to know more about this topic” pile.

[1] I don’t go out to look for this stuff. It accumulates on my “I need to know more about this topic” pile.

Very interesting arguments here, Jeffrey. I agree with your assessment.

Jeffrey,

Three observations.

First, the tests have been around for since the 1970s and the genesis of them was the CA Standard Practice Manual which first delineated how to apply the tests. There has been some evolution of the tests since that time, but the same basic tests are used in most states across the US. Some states will emphasis one test more than others though.

Second, some non-energy benefits can be quantified. A good example is a low flow shower head. It reduces the flow of hot water so saves in natural gas usage, but it also reduces cold and hot water usage which can be quantified by figuring out the reduced water flow times the rate you pay for water.

Third, most people unless they have gone to college and taken accounting, business or finance classes have a hard time with benefit-cost analysis except in a general way, no matter what methodology is used.

Finally, I agree with you. It’s past time to get more critical thinking into the discussion of benefit-cost analysis for energy efficiency.