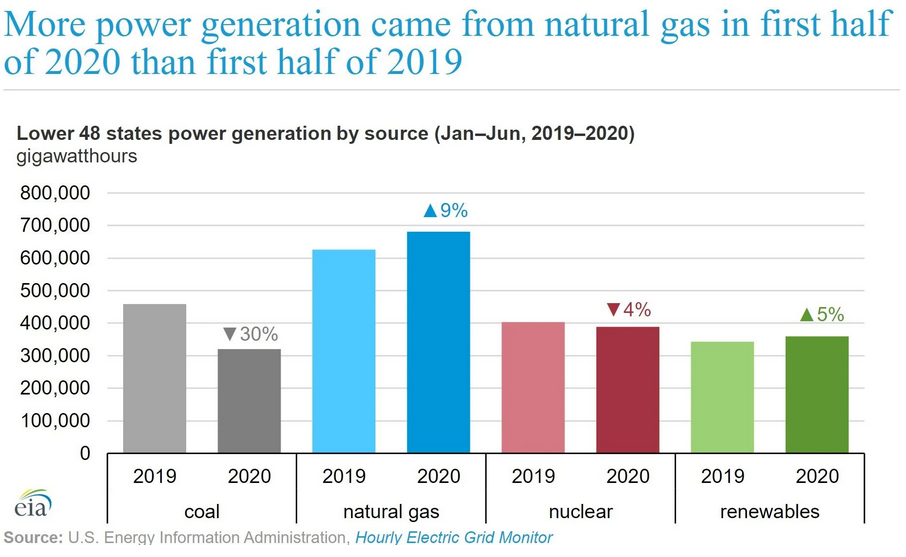

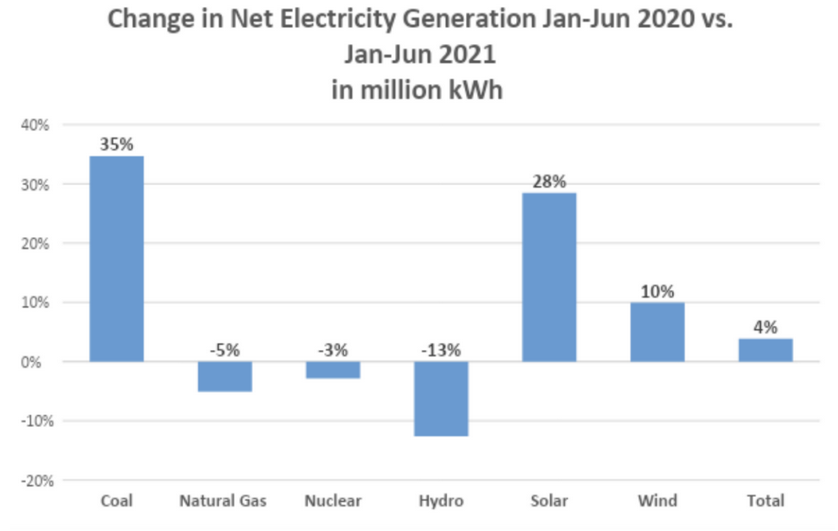

It has been a frothy year for the energy industry, and it will continue well into next year and beyond. How far? Heh heh. Let’s start with coal. After plummeting 30% in 2020, consumption bounced back, gaining 35% in 2021. Doing the math, that doesn’t quite get coal back to 2019 consumption.

Coal plants are still closing at a breakneck pace, so consumption in the United States is bound to decline in the long haul, but will load balancers and utilities be able to keep the lights on in 2030? This is a concern to me because no source of electricity is more reliable, stable, and secure than a mountain of coal next to a power plant or a year’s worth of U-235 in a nuclear reactor plant located next to a river or lake. The next decade will tell us a lot, and I’m betting it will be good times for customer-sited generator manufacturers and service providers.

Coal plants are still closing at a breakneck pace, so consumption in the United States is bound to decline in the long haul, but will load balancers and utilities be able to keep the lights on in 2030? This is a concern to me because no source of electricity is more reliable, stable, and secure than a mountain of coal next to a power plant or a year’s worth of U-235 in a nuclear reactor plant located next to a river or lake. The next decade will tell us a lot, and I’m betting it will be good times for customer-sited generator manufacturers and service providers.

The Wall Street Journal reports coal consumption will exceed 2019 levels this year and continue to rise worldwide through 2025, which is about all the further anyone can project anyway. Crude oil production is rising but struggling to match demand. Worldwide consumption will be a whisker short of 100 million barrels a day. A supertanker holds 2 million barrels. 😮😬 That is a lot of erl.

By the way, to all the cranks who think efficiency, demand management, and grid-interactive efficient buildings are giant wealth transfers from some customers to other customers – what do you think about the need to spend tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars on a standby generator or other distributed resources because there isn’t enough supply at the right times to go around?

Keeping the Lights On

I live near Iowa and Minnesota, which are both pretty well saturated with wind turbines that produce roughly 40% of the electricity; a substantial portion of which may be exported to neighboring states. Other states like Michigan are just getting started with wind deployments. For example, per EE News (acquired by Politico from which I can’t find a link to the article), Consumers Energy has a mere 80 MW of installed wind capacity with plans to ramp that up to 6,000 MW by 2040. This is an enormous shift away from dispatchable, reliable thermal power plants like nuclear and coal when combined with similar paths in other states and utilities.

Question: Is anyone looking at the big picture, as in, regional transmission organizational footprints, and asking, can we keep the lights on when all states jump on this wagon? I don’t think so. Moreover, the same Wall Street Journal article notes the clean energy needs to grow from around $1.1 trillion invested this year to $3.4 trillion per year through 2030. Why is it? My guess is pretty simple: it’s too expensive.

This will become a significant problem. I am telling anyone who will listen and, to pile on a little more in case readers aren’t alarmed enough, this is before shifting transportation to electric vehicles.

We are seeing the tremors now. The Wall Street Journal writes wind and hydro are failing to meet projected output, putting greater pressure on fossil-fuel plants, which are rapidly being decommissioned and razed.

The Wall

As written before, renewable energy, storage, and electric transportation are much like baby tigers in their infancy. They are easy to control and maintain at a small scale. When they grow up, they are an altogether different beast. The IEA reports, “The world isn’t investing enough to meet its future energy needs, and uncertainties over policies and demand trajectories create a serious risk of a volatile period ahead for energy markets.” Ramping up renewables requires much more mining for everything from wind turbines to batteries. And it isn’t “clean.” While the cost of solar capacity and production has plummeted, it has been on the back of coal-fired power from China, which produces 75% of the world’s polysilicon, per The Wall Street Journal.

Crude consumption is also rising, in part because coal shortages are making it necessary in foreign nations to generate electricity with it to keep the lights on. In summary, we’re already scrapping for every fuel, and soon, every dispatchable power plant available to keep the lights on. The result is that natural gas, oil, and coal prices are up by 71%, 121%, and 28%, respectively. Most of us, including me, don’t remember or have never experienced energy price shocks that are starting to buzz.

The wall is the price wall of dual capacity – some kind of unicorn electricity storage technology, backup thermal power plants, or tens of thousands of miles of high voltage transmission lines that local folks fight tooth and nail.

What About Efficiency and Demand Management?

As usual, efficiency and demand management get no mention as energy resources. The word doesn’t even appear in The Wall Street Journal article.

Energy users have little control over energy policies, pandemics, pandemic policies, foreign activities, energy exploration, pipeline construction, electricity sources, and who controls vast swaths of minerals, industrial and exotic metals, and materials. Energy users can take control of consumption and peak demand, and therefore, costs.

Similarly, utilities will need to re-diversify their portfolios to include load management that is flexible to match renewable generation gyrations. Otherwise, price-shock revolts are on the way. Satisfying stakeholders was easy when renewable sources were being built because an excess of depreciated generation remained to fill the valleys. That tiger is growing up fast.

We must start yesterday to avoid the equivalent of gasoline lines and price controls, which merely create another problem: shortages.

This analysis is excellent. The attack from the top against nuclear, coal, and natural gas, as a side-effect, results in provoking a type of market failure. The market failure is artificial in the sense that it is legislatively driven. Minnesota’s approach of protecting natural gas because the alternative is to extensively build out the electric system to meet peak winter demand is well grounded. Take away coal and demand for natural gas at the generator level shoots up. That substantial increase in demand means competition for available supply that drives up cost to civic consumers of natural gas. Price is up 10% in Oregon in new residential rates, overcoming the previous downward trend due to new lower cost supply from fracking. But the pressure behind this rate change is much stronger than the initial rate effect – the regulatory system is designed to dampen rate increase and spread it over time. Sizable civic customer rate increases are likely to continue for both natural gas and for electricity.

Of course, DSM energy conservation works well and with full funding (a fully social program, without regard for household income) would make a great social program that would reduce demand and consumption for energy, and similar commercial, industrial, and institutional programs would lower consumption and demand overall. But it only works through a fully social program like the Green New Deal. We do not have time for incremental change, and our climate adaptation infrastructure is non-existent.