This week’s Energy Rant is courtesy of guest writer, Brian Uchtmann, Evaluation Engineer at Michaels Energy.

Energy efficiency programs remind me of a joke about economists; here is my version for evaluators. Feel free to use this joke at your next party[1].

Two energy efficiency program implementers and an evaluator go on a deer hunt. In the distance, they see a magnificent buck. The first implementer aims and fires. The evaluator yells “Missed, way too high!” and jots down a few notes. The second implementer lines up and shoots. The evaluator yells “Missed, way too low!” and adds an entry into the log. The deer walks away.

After a pause, the evaluator dances a jig, spilling paper everywhere, shouting “Got’em! – let’s eat!”

Last week, Jeff Ihnen noted that utility energy efficiency programs act as substitutes for supply-side resources, but efficiency gets no utility profits. Worse, energy efficiency resources carry more risk than brick and mortar assets. He is not wrong[2].

There is a problem[3] with considering energy efficiency completely on par with conventional supply-side resources. COST. More precisely, the avoided cost. We don’t know what it is. It is hard to plan based on cost information you don’t have.

Regulated utilities in the United States do not function in a free market, but they still work pretty well. There are many factors that contribute to the low price of electricity in the United States relative to other countries; domestic fossil fuel energy supplies, large markets, and effective and efficient state-level utility regulation[4]. Generally, utilities are granted a rate of return sufficient to raise capital to build infrastructure. Public rate hearings allow a forum for adverse parties to oversee the prudence of these investments and allocate the costs to different types of customers. This cost is known. The avoided cost is unknown, in many cases[5]. If we don’t figure it out, then we are making things worse.

Get the cost-benefit right about right, or get in the bread line.

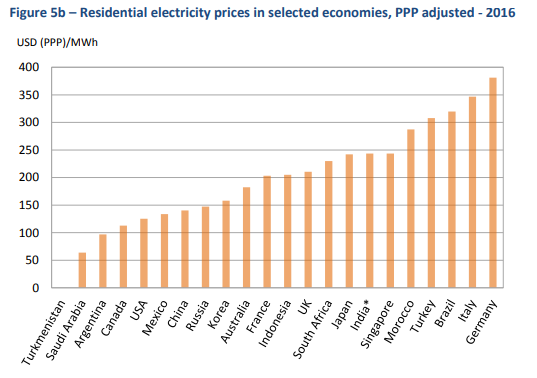

Many people in our industry complain about how our regulatory system works, but generally the cost is allocated pretty well, and the investments make sense. How do I know? We have cheap energy relative to the rest of the world, and we don’t have the electric equivalent of bread lines. Consider this chart from the International Energy Agency WORLD ENERGY PRICES (2018 edition). The US is down on the far left, in the cheap zone, if you can’t find it. When the price of a good is too high, this typically means that the supply has been constrained, and someone is collecting “monopoly rents” – our system was specifically designed to avoid this. And we do.

On the other hand, when prices of a good are too low, either because of price subsidies or other market distortions, consumption goes up. If there is insufficient supply to meet this consumption, demand is limited by making people wait in line (in the case of consumer goods) or suffering brown-outs and black-outs (in the case of electricity). These situations are tragic, graphic, and avoidable.

As noted, the utility sector in the US does not operate in a free market to provide price signals to consumers and suppliers. But it does work. We have built a system that protects us from monopolist overcharging, and from over-zealous price controls that would reduce demand through brown-outs.

So how much energy efficiency should we have?

This is the 7.5-billion dollar question[6]. It is an important one. When utility energy efficiency programs are underfunded or ineffective, we all lose. Utilities receive a guaranteed rate of return for investment because of the need to raise capital. There is no mandate, or even rationale, for giving utilities profits just because we are nice. Regulators and stakeholders are working hard to reduce the amount of money that utilities make. Energy efficiency is not the enemy of utilities any more than clean water is. Utilities operate in a space that is supposed to benefit ratepayers and customers. Normal infrastructure, fuel costs, pollution, energy efficiency, and utility profits all play a factor for regulators in this market.

That is the reality of regulated industry. We don’t have breadlines or rampant gouging because our system works. But this system only works when we have reliable information to make investment decisions. The conventional wisdom is that energy efficiency is about half the cost of supply-side energy resources. Business and economic interests should be demanding more energy efficiency. In fact, they do. People demanding low electric rates are actually demanding more energy efficiency investment. They just don’t always know it. So, why don’t we do more?

I think there are two reasons. The first is that we don’t do a good enough job showing the math on cost-effectiveness. We need to consider attribution and avoided cost rigorously, and provide regulators and stakeholders certainty that the money is being well spent.

The second is that energy efficiency can be hard. Throwing an additional dollar at energy efficiency is not enough to ensure that ratepayers benefit. Some programs and projects are terrible. My best guess is that I have done about 1,000 site visits for evaluation and energy efficiency studies, and I have seen projects that have done nothing to help the ratepayers that fund them. It’s rare, but I have seen it. When we see it, we need to fix it.

To address these issues. We need robust and competent evaluation of energy efficiency programs. We can’t just aim wildly and hope that, on average, we hit the magnificent buck (cost effectiveness target). We need to adjust our programs and funding until we actually hit the deer. Now let’s eat.

[1] Not recommended.

[2] His correctness factor (CF, a made-up value) was about 0.87, a slight decrease from the last post’s CF, but still above industry average. See stranded assets, Enron, Public Service Co. of New Hampshire et al.

[3] Several problems.

[4] This is not a joke. This is done well in the United States.

[5] In fully vertical markets, the avoided cost of power from other sources is often known.

[6] Ratepayer funded energy efficiency spending, 2015.