Virtual power plants (VPPs) represent a considerable slice of the clean energy race these days, and for a good reason: policy continues to favor intermittent renewable energy supply over baseload nuclear and dispatchable natural gas assets. Load needs to follow supply. Theoretically, we would need a lot of load flexibility for many hours and sometimes days to keep the grid energized with, mmm, 50% renewable energy. As of 2021, the renewables slice of the supply pie was around 13%, so there is a long way to go.

The DOE’s Virtual Power Plants Commercial Liftoff report declares the United States needs 80-160 GW (gigawatts) of VPPs by 2030 – “tripling current scale.” The report is well concealed on that website, like a camouflaged owl, but I hunted down a link for you here. You’re no match for me, Hootie.

Give us some perspective, Jeff. What does 80-160 GW look like? Is it a pebble or a mountain?

Give us some perspective, Jeff. What does 80-160 GW look like? Is it a pebble or a mountain?

It’s closer to a mountain – slow-moving ones, like the Himalayas. The coincident peak load in the United States is around 750 GW. A large nuclear power plant, e.g., the Vogtle plant, is each around 1 GW in capacity; therefore, our peak load equals about 750 large nuclear power plants.

Demand Response Status

Demand Response Status

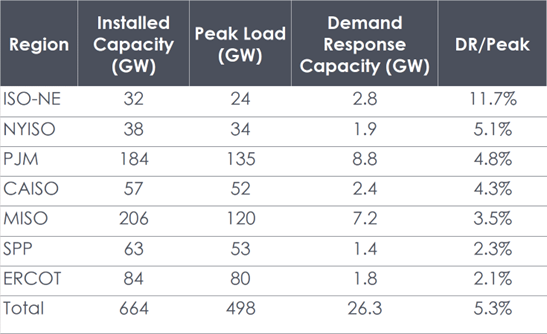

We need to get to 80-160 GW of flexible loads on a grid with a total load of 750 GW. I’ll pick the middle of the target, 120 GW, which is a measly 16%. Where are we at today? Five percent (5.3%)[1].

Breaking Down Demand Response

Breaking Down Demand Response

PJM is the largest regional transmission organization and load-balancing authority in the upper 48 states. A PJM report published last week shows that manufacturing is the predominant means of load management via manual production curtailment (chart below). This is not a viable load flex resource for VPPs. Calls on manufacturing interruptions might be triggered once or twice a year for an emergency response to avoid rolling outages.

This PJM demand response allocation is typical of other allocations I’ve seen. Considering most of the load management under contract today includes a significant loss of service and rare dispatch, at best, 10 GW of potential VPP loads are under control. Therefore, the target isn’t merely tripling what we have today. It’s much closer to a ten-fold increase. Reality check: not going to happen. But let’s give it the old college heave-ho.

This PJM demand response allocation is typical of other allocations I’ve seen. Considering most of the load management under contract today includes a significant loss of service and rare dispatch, at best, 10 GW of potential VPP loads are under control. Therefore, the target isn’t merely tripling what we have today. It’s much closer to a ten-fold increase. Reality check: not going to happen. But let’s give it the old college heave-ho.

Speaking Load Management

Load management, energy efficiency, and electric vehicles are common threads among folks in our industry. Our 0.1% of the population eats, sleeps, drinks, and loves them, and so will everyone else once they wake up. Well, no. Maybe 20% of the population can be reached with the right language and messaging to participate in the cause. The other 80% need added benefits, no loss of service, and financial gain. Loss of service means hassle, discomfort, lost productivity, pain, or any combination of the four. Examples include working in dim, hot conditions, doing laundry in the middle of the night, or shutting down a production line.

Those 80%, the “normal” people, don’t want to manage their lives around their utility bills and tariffs that describe how charged amounts are tallied. They want inexpensive, reliable power to live their lives. People don’t like disruptions to their routines. For example, a few years back, our parking contracts were changed from having a reserved spot every day with my name on it to an open free-for-all. That reduced some costs for the city because they didn’t need to roll a truck to ticket someone who parked in my spot or someone else’s. However, the benefits were not passed along to customers through cheaper rates. That is not how rate reform should be done.

Tiered Load Management

I suggest a tiered approach to load management in this order:

- Rates

- VPPs

- Interruptible

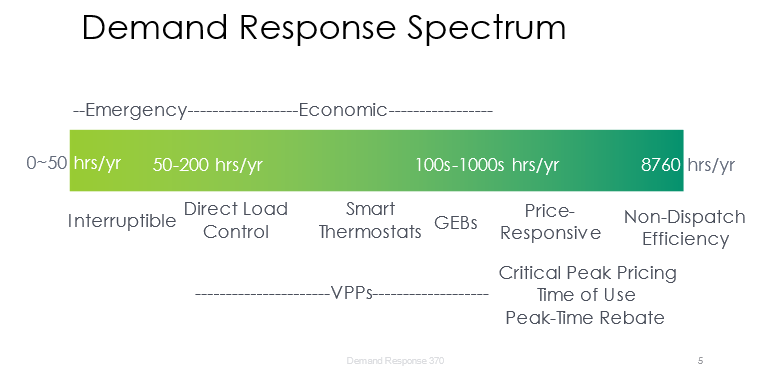

As luck would have it, that is the same order as I suggested in Leveling the Skateboard Curve two years ago – right to left, from more frequent to less frequent. This time, I included where the VPPs line up.

Like the parking case, load management should start with rate design—stiff time-of-use (TOU) and/or demand charges for residential, small, and medium-sized commercial customers. Customers must have the means to avoid high charges, as I described a year ago in Modern Electric Rates from the Slide-Rule Era.

Like the parking case, load management should start with rate design—stiff time-of-use (TOU) and/or demand charges for residential, small, and medium-sized commercial customers. Customers must have the means to avoid high charges, as I described a year ago in Modern Electric Rates from the Slide-Rule Era.

I suggest providing customers with billing totals for the old tariff and new tariff for at least a year so they have an opportunity to reduce their bills. In one conversation at last week’s Peak Load Management Alliance conference in Portland, one utility representative said they were given the opportunity to switch tariffs, but the TOU tariff would increase their bill, so almost no one, including utility people in the load management department, changed rates. Well, rates should increase when switching to a TOU tariff. That’s the point. HOWEVER, customers need a chance to overcompensate and reduce their bills.

Prepare for squawking because 1) people don’t like change, and 2) somebody will pay more when others pay less because regulated utilities have revenue requirements. I’ve read and heard arguments that such changes unfairly impact some customer classes, such as older adults, income-qualified, and others, because they may be home all the time without options to curtail consumption during rush hour. However, since COVID-19, many people have been home all the time. Folks need to be informed to understand how pricing works at the wholesale level, which is essentially passed through to retail, and they will appreciate that. In a distant second, technology can help automate load reduction during peak times.

Ok. I have too much more to say to cover this all this week. To be continued next week – specifically, strong VPP attributes.

[1]Table sources: installed capacity and demand response: Peak Load Management Alliance; Peak load: Bing topline search results.

Demand Response Status

Demand Response Status Breaking Down Demand Response

Breaking Down Demand Response