About twenty years ago, I moved into my first home, which sits on a beautiful lot where the cattle used to graze. When you think about it, all homes sit where wildlife used to frolic, but I digress. The point is, a first-time homeowner, especially one with a substantial lot and a long driveway, is in for a few surprises. I remember saying $10,000 checks were flying left and right, and that’s not even for the mortgage payments. Driveway: $5,000. Lawn seeding: $2,000. Mowing tractor and snow removal equipment: $7,500. There were at least twice that many nickels and dimes. I don’t remember them all, but you get the picture.

Fortunately, these were one time investments that served us well. What about energy costs? For the home, it wasn’t bad because, of course, efficiency was built into everything. However, for commercial real estate, it is a serious issue. And unlike the nickels and dimes above, waste is waste for which tenants and property owners get zilch – no asset, no added value, no added comfort, and in some cases, discomfort.

Myopically Awful Ideas

I’m more sensitive to wasting energy and money than the average bear, but consider some of the lamebrain decisions property developers make. My first rented space here in La Crosse was affectionately called the icebox. Concrete. Cold. It had a propane-fired furnace, and the floors consisted of precast, hollow-core slabs as shown below.

Certainly, there are ways to use this construction and not waste hordes of energy, but the dummkopfs who designed the icebox had a great idea – they avoided paying for ductwork and used the cores of the concrete panels for air delivery. The concrete had a voracious appetite for heat, and much of it was conducted to the outdoors before it ever made it to the room.

The second place I rented was quite modern at the time, built in the mid-1990s. Everything about the place was good, except they made the incredible, short-sighted decision to install electric baseboard heating.

Similarly, here in La Crosse, per my understanding, a developer repurposed a former office building into a swanky apartment/condo complex and blew it with electric resistance heating. It’s the icebox sequel, but electric heat rather than propane. This property is targeted for the young professional with a load of college debt. Do you think they want to pay 30% of their rent on the electric bill?

The years of vacancies or lowering of rent will cost the developer for years. Either way, the tenants are going to move in and after the first severe heating month, start looking for another place that is either less expensive to lease, less expensive to heat, or both.

Blown Opportunities

In our world of the regulated energy efficiency programs, these developers would get no financial incentive to put in natural gas heat and efficient cooling, or cold-climate heat pumps. Talk about blown opportunities and market failures. There has to be a way to avoid these energy catastrophes.

I guess it depends on how one defines market failure. The market works. Tenants walk.

Commercial Real Estate

Energy costs for commercial real estate (office buildings) are a big deal relative to the lease cost. Even in New York City, where you might think commercial real estate leasing costs tower over utility costs, energy is a significant portion of the tenants’ cost – as much as 20%, for example. This percentage is not unlike ratios we experience with our leased spaces.

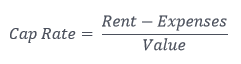

One of the reasons I write this blog every week is to exercise my brain to make sure it still works. In commercial real estate, a key performance indicator (KPI in our lingo), is the cap (capitalization) rate, which equals the net operating income divided by the value of the property. Very simply:

Expenses vary by lease type. In our experience, “triple net” is the lease of choice from our property owners. The three “nets” include property tax, insurance, and common area maintenance (CAM). These are divvied up by proportion of the building rented. Energy costs are often passed through to the tenant as well.

Expenses vary by lease type. In our experience, “triple net” is the lease of choice from our property owners. The three “nets” include property tax, insurance, and common area maintenance (CAM). These are divvied up by proportion of the building rented. Energy costs are often passed through to the tenant as well.

Tenants and the Total

We can see that a tenant can afford dollars for a rented space. It doesn’t matter whether the dollars are going to property taxes, CAM charges, or utility bills. If any of the expenses are reduced, the rent can be higher, all else equal. When the rent is higher, the cap rate would seem to go down, but it doesn’t. The property value increases, and the cap rate remains roughly the same.

The cap rate is a measure of risk, like interest, the yield on a bond, or dividend paid for a utility stock. This site has it dead wrong when they say “a high capitalization rate implies lower risk while a low capitalization rate implies higher risk.” I don’t think I’d send my budding real estate brokers to learn from them. Investopedia gets it right. A lower cap rate signifies less risk and higher property value, all else equal.

The cap rate is just one metric for determining property value. One could see a high cap rate from an energy hog of a building, and behold, now there is a great opportunity! Remember, tenant costs include everything. They can pay rent, or they can pay for wasted energy. Reducing waste will increase rent and property value over time – in addition to having a lower cap rate as a result of tenants fleeing the energy boogeyman.