This is the fourth in a series of posts on grid-interactive efficient buildings (GEBs). Here is a summary of the series:

- August 23 – Why GEBs? What is it, and why do it?

- August 31 – GEBs are difficult to achieve, beyond efficiency that should be done regardless.

- September 7 – What will customers think of this madness?

Let’s peek at where we’ve been and where we are going. This series is based on a list of challenges noted in DOE’s National Roadmap for Grid-interactive Efficient Buildings:

- Consumer awareness (Covered 07SEP21)

- Complexity (Covered 31AUG21)

- Utility interests (Today)

- Regulatory models

- Policymaker ignorance

A TOU Cautionary Tail

This post will explore utility interests, but first, I want to backpedal a bit based on some findings after last week’s post. Last week, I noted some estimated savings for time-of-use (TOU) rates. Estimates vary widely, but one study showed that for every 10% difference in the ratio of on-peak to off-peak pricing, customers used 6.5% less energy on-peak. For example, if on-peak prices from 4:00 PM to 8:00 PM are 15 cents and off-peak prices are 8 cents, the on-peak savings would be 15 / 8 x 6.5% = 12.2% on-peak savings.

Last week, I saw the results of a pilot project that is not yet public, so trust me on this. Those rates were 70 cents on-peak (four hours in the morning and four hours in the evening) and 7 cents off-peak. There were some shoulder rates (in between), but that’s beside my point.

My point is this: Why do TOU rates and GEBs anyway? Go back to the first post –for electrification and to support a low-carbon (renewable energy) grid. When I look at these rates, I think natural gas, please. What do most city folk do in the morning? Shower, preferably with hot water. In the evening, they use more hot water and heat living quarters in wintertime. Yes, these wild price ratios can be managed to some degree with cutout controls for water heaters, unless you have teenagers that empty the water heater during their 15-minute showers; and skip the heating and cooling setbacks to coast through the peak period. But normal people (see last week) will say, to hell with that. Just give me natural gas for the simple life. Look out! You have to look at the big picture, which includes alternative fuels!

Utility Interests

I’d love to be a fly on the wall in board meetings of investor-owned utilities. Do they know the efficiency industry exists? If they do, what percentage of their viewpoints of us are negative?

Utilities make money by building things, adding to their rate base (equity), and charging a rate of return on that equity to customers at about 11-12%.

What is the purpose of efficiency programs? When they started 40 years ago, the objective was to conserve fuel. Everybody, including utilities, liked that because wasting fuel is a loss for everyone. It’s a pass-through cost for utilities and not an earnings generator.

From billing rates to investment, broken-down regulatory regimes disincentivize utilities to promote GEBs. Rates that promote shaping, shifting, or shaving, result in less infrastructure to keep the lights on in periods of surging demand. Less infrastructure, including transmission, distribution, substations, and generation[1], means less equity and less profit.

The archaic regime also disallows, or at best, makes it extremely painful for utilities to invest on the customer side of the meter for things like GEBs.

Therefore, utilities are left with keeping peak demand low(er) for major customers, so there are no uprisings while the legislature is in session. One way to assuage pricing fury from large energy users is to deploy interruptible tariffs to decrease demand rates all the time in exchange for curtailing consumption when asked. Money is saved (economic demand response) by avoiding expensive pass-through charges for generation provided by peaker plants.

In sum, people vote, and large users lobby. The indirect benefit to keeping utility-system peak demand in check is to keep the torches and pitchforks in the shed. That is what I’m seeing for utility interest in GEBs and keeping prices in check. Play the game by the regime in place. That is what any smart business does.

Economy of Scale

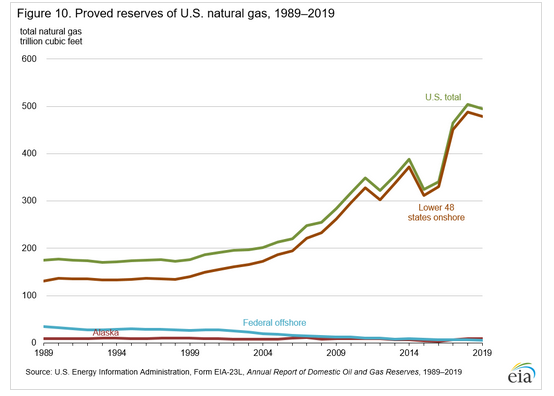

As mentioned above, 40 years ago, everyone wanted efficiency because the alternative was running out of energy sooner. Energy prices were soaring. It was a national security issue. Since then, confirmed conventional fuel supplies have grown. As shown in the following chart, we’re finding energy faster than we’re using it. Proven crude oil reserves look about the same as the natural gas chart below. We have about 400 years of coal in the ground and unknown nuclear reserves.

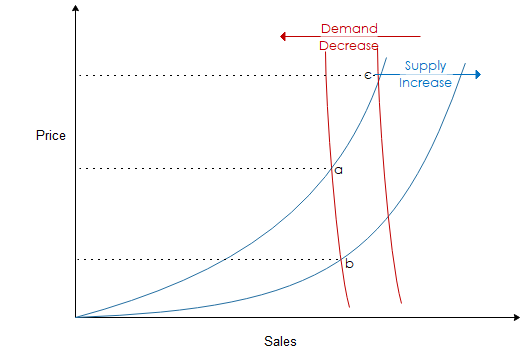

As demand for these fuels shrinks, prices drop, all else equal. As the supply for these fuels increases, the price drops. This is shown in the illustration below. The intersection of supply and demand curves sets the price. For instance, a supply increase is demonstrated by a lower price from point a to point b. A demand decrease is demonstrated by a lower price from point c to point a. By increasing supply and decreasing demand, the price would fall all the way from c to b.

However, this is not how it works with utilities, which have revenue requirements based on funding operations and equity and debt financing. Oh no! These curves don’t work at all for sales of electricity, BECAUSE of the revenue requirement. If energy sales shrink, the price goes UP to make up the lost revenue. The purpose of decoupling is to separate revenue (prices) from sales. Anyone can correct me if I’m wrong, but even without decoupling, utilities eventually get the “lost” revenue through rider adjustments.

However, this is not how it works with utilities, which have revenue requirements based on funding operations and equity and debt financing. Oh no! These curves don’t work at all for sales of electricity, BECAUSE of the revenue requirement. If energy sales shrink, the price goes UP to make up the lost revenue. The purpose of decoupling is to separate revenue (prices) from sales. Anyone can correct me if I’m wrong, but even without decoupling, utilities eventually get the “lost” revenue through rider adjustments.

I believe I’ve demonstrated that traditional supply/demand is out the window for the electricity market. The next phase is going to be…? Yes! Regulatory models to turn things inside out after being flipped upside down.

[1] To some degree in fully regulated states. It’s complicated.