Over the weekend I was reading this white paper by ACEEE, and as almost always, a number of responses came to mind.

With the passing of years I observe that as people age, they fall into perhaps three categories: (1) the curmudgeons – the glass is ¾ empty and don’t tell me it isn’t (2) cynical cranks with ideas and (3) Chrissy Snows. Engineers, for example, fall into the first two groups – or they go to law school, get into politics, and turn into a Chrissy Snow. Chrissy Snows, as with everyone, are mostly good people, but they live in fantasy land in terms of what’s really going on in buildings regarding energy efficiency.

As I picked through the ACEEE paper findings, I started responding with comments. The first finding is that the US modestly improved spending on energy efficiency programs. I thought, big deal. Consider other institutions that are spending other peoples’ money like crazy, faster and faster. How is this working for us? Bupkis.

In the next item, ACEEE evaluates savings from programs, and this is improving, but there is an error. They report 22,000 GWh, or 22 billion kWh annually, and 20,000 MMTherms, or 20 billion therms, virtually the same number. The ratio of kWh to therms should be very roughly 50:1, so I’m guessing this ACEEE estimate has gas savings high by 100x. Tip: watch out with therms and MMBtu. The therm, at 100,000 Btu seems like an innocent, metric-like number, but it’s the devil in disguise – very easy to be off by one or two orders of magnitude (factor of 10).

Next is on to energy productivity measured in gross domestic product per unit of energy consumed. This improved 5% to $157 per million Btu consumed. The cynical crank in me thinks this metric is more a function of the economy, energy prices (gasoline), and our somewhat volatile manufacturing sector. Energy efficiency has very little to do with it. And as an evaluating engineer, I calculate things to put numbers in context for ballpark consideration. This energy in Btu would be source Btu, essentially a form of energy that burns – solid, liquid, gaseous fuels. I would guess that blending all these sources together to develop a blended cost per million Btu results in a cost that is approximately the same as the cost of a retail natural gas[1]. Therefore, an MMBtu at $7-8 would mean spending on energy is about 5% of GDP (7÷157). Seems reasonable to me! So, in this metric of MMBtu per GDP, we are talking 5% change in 5% of the economy, so to speak- very volatile. A tiny error can make a big difference.

And by golly, I actually looked this up after the fact, and indeed, spending on energy as a percent of the economy is 5%. Touché. Onward.

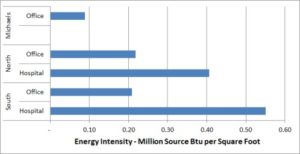

The next metric that caught my eye was that energy intensity for commercial buildings had improved by 3% from 2011 to 2012, at 214,000 Btu per square foot. My first reaction was this is absolutely woeful, but after checking it against the benchmarking data we use, it is reasonable. I looked at large office buildings (low end energy intensity for commercial buildings) and hospitals (high end) for both hot southern climes and moderately cold northern climes. To these, I added actual energy intensity of our office space in La Crosse.

At this juncture, I’m too lazy to look, but I think consensus claims there is 30% energy savings potential in commercial buildings. With data presented in the bar chart, I think of my brother telling me when I was a kid, “No sh**, Sherlock”. I.e., DUH! Last week I quipped buildings are hemorrhaging waste. Indeed they are.

Believe it or not, our La Crosse office is not crazy efficient. We have enormous west-facing, plain Jane windows (terrible from an energy perspective), a mediocre chiller, and a status quo air handling system in a 100 year old building with no insulation. The secret sauce: appropriate systems design and control.

This brings me to the last thing I will mention from this report today: ACEEE ranks the US very favorably for energy codes. Hello Chrissy Snow. Chrissy, meet number 2, the cynical crank. Energy codes are NOT like energy standards for refrigerators and EPA fuel economy for automobiles. The latter objects can be tested in laboratories and precisely measured. Buildings, under the jurisdiction of codes, can be tested as well, but they generally are not, and if they are, it is probably done poorly.

Chrissy Snows think if building codes are written down they will be implemented. Sorry. Energy codes aren’t even like speed limits that no one follows. They aren’t like the legal drinking age either. These laws present limits on citizens, albeit not precisely. The not-reckless people among us tether themselves to the speed limit with varying lengths of rope. I am guessing high schoolers don’t have a chance with a tampered ID either. Comparatively and metaphorically, most buildings resemble a buzzed 15 year old with the family sedan careening down a major thoroughfare at twice the speed limit. Call the cops!

[1] Rule of thumb alert.