I attended Electric Power Research Institute’s Electrification 2022 Conference in Charlotte a couple of weeks ago. As a critical thinker and engineer, I often listened and thought, what about this or that, what does that look like at scale, or what you really need to do is ___.

Silos of Excellence

Everyone seems to think about an endpoint where the entire country will run on solar panels, windmills, heat pumps, and electric vehicles. No one talks about what must happen between here and there. The silos of excellence include:

- Our industry and associated tiny departments representing utilities expect a 100% electrified world in just a few years.

- Vast expansion (I did not say conversion on purpose) of parasitic solar and wind generation by investor-owned companies.

- An electric storage industry that is grabbing all they can before someone figures out that will never be the answer to bridging gaps of intermittent renewables – at a cost that comes close to what developing countries will get for power using coal.

- A vacuum of thought on when and how power is used and when and how renewable energy is generated.

- Grid operators and utilities are reactive and stuck with guessing what the future holds.

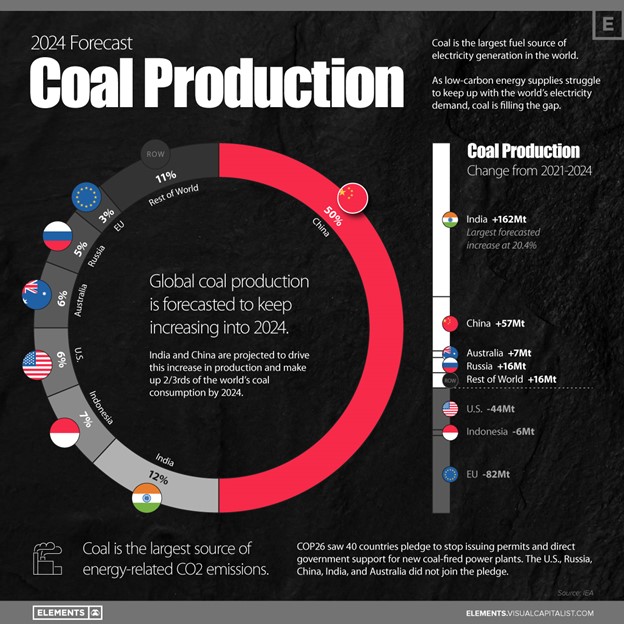

As a garnish, if the United States and European countries electrify everything, it won’t matter from an emissions perspective because China, India, and Indonesia have already blown past the U.S. and Europe in coal consumption. They do not intend to pay more for renewables, storage, and a full set of backup generators to keep the lights on. If it were cheaper or improved life, comfort, and productivity, it’s good. There is some of that, for sure. But much of it will cost dearly.

Heat Pumps

Heat Pumps

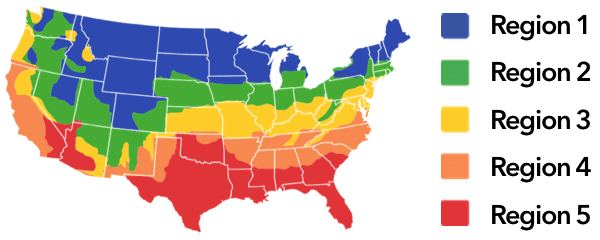

I attended a workshop on heat pumps. Like everything, heat pumps have their place for specific use cases. I agree with this website that air-source[1] heat pumps are suitable for stand-alone applications in Region 3 and warmer climates from the map below. One demonstration project from the workshop included a new home that drew an average peak demand in the coldest weather of 7-8 kW for the heat pump alone. The kW plot showed cycling between the heat pump and resistance (toaster) coils[2].

Yeow! That compares to a summer peak of about 5 kW per home, not necessarily coincident with grid peaks.

Other options include hybrid heat pumps that use natural gas in the coldest weather of the coldest climates. This is an excellent idea for curbing electric demand and having a backup when the windmills aren’t turning. One guy said that would never work because it would result in a death spiral for gas utilities. Huh? Electrification would result in a gas death spiral. Remember the death spiral for electric utilities? That was less than ten years ago. Such predictions are wildly off target.

Other options include hybrid heat pumps that use natural gas in the coldest weather of the coldest climates. This is an excellent idea for curbing electric demand and having a backup when the windmills aren’t turning. One guy said that would never work because it would result in a death spiral for gas utilities. Huh? Electrification would result in a gas death spiral. Remember the death spiral for electric utilities? That was less than ten years ago. Such predictions are wildly off target.

A long-term and better option for the northern two regions may be ground source heat pumps – a forty-year-old technology that had boom times in the late 90s and aughts. Ground source is a better option because the heat sink (earth) temperature is much more stable than air source’s heat sink (outdoor air).

Some public utilities have successfully deployed lease-to-purchase agreements for ground-loop heat exchangers. Financing periods run 20 years and are included on customer bills, removing a huge barrier. Unlike HVAC equipment with roughly 15-year expected lifetimes, ground loop heat exchangers are projected to last at least 50 years. Utilities, including investor-owned, and their regulators need to explore this for any extensive penetration of HVAC electrification up north.

Electric Vehicles

Cold weather is like a bad cold to the electric vehicle, stunting its performance by reduced battery capacity, greatly increased need for battery power for heat to keep windows defrosted, and concurrent increased rolling resistance of frozen, stiff tires. But aside from that, the sun shines during the day – yes? Where are EVs during the day? In some parking lot, garage, or ramp at work, or on the road to get provisions or transporting kids. EVs get charged at night, to the tune of 80-90%. Do you see a problem here?

The industry and federal government are focused on fast chargers along traffic corridors so EV enthusiasts can drive coast to coast without hassle. Not many people drive coast to coast. This reminded me of a recent article in The Wall Street Journal; I Rented an Electric Car for a Four-Day Road Trip. I Spent More Time Charging It Than I Did Sleeping. Before you go off on the story of these two young ladies behind the story, they are ordinary folks and not EV nerds. Like the vast majority of common people, they do not live for technology or plan their life around a battery and the electric grid.

The car was Kia EV6 with a 310-mile range. They mapped the course with public charging stations from New Orleans to Chicago, and back. Most of those stations were Level 2, requiring eight hours for a full charge, as opposed to refueling with 87 octane in a few minutes with time to spare for the kids to return from the truck stop bathrooms. They reported spending $175 for charging versus $275 it would have cost for gasoline in a Kia Forte.

They spent time hunting down various “fast” chargers at dealerships and even a Harley store. They called day one an electric car hazing – not bad humor! One woman they met described a harrowing trip in her Volkswagen ID.4. She had to be towed twice while driving between her Louisville, Ky., apartment and Boulder, Colo., where her daughter was getting married. That won’t sell many cars.

After leaving Chicago, one tells the other, “I might write only about the journey’s first half. The rest will just be the same, I predict.” To which the other replies, “Don’t say that! We’re at the mercy of this goddamn spaceship.” She still hasn’t mastered the lie-flat door handles after three days. Very hilarious.

On the way out of Chicago, they started with a 100-mile cushion to reach the first charging destination, but that cushion dwindled to 30 miles. “If it gets down to 10, we’re stopping at a Level 2.” Geez, this sounds like fun! The rest is hilarious as they run out of juice after shutting down the AC and other ancillaries to get as far as they can.

To be continued…

[1] Exchanges heat with air outdoors.

[2] Slides and details requested from EPRI.

Allow me to chime in for my fellow EV enthusiasts and provide a rebuttal for some of your EV comments.

Regarding cold weather performance, yes, EVs without heat pumps (using elec resistance heaters) take a 30-40% range hit in winter for sure. Heat pump cars (for the parts of winter above 20F or so) are more like 20-30%. It is definitely a barrier to EV adoption in cold climates.

For areas with a lot of wind generation, the fact that EVs charge overnight is a very good thing, since utilities need to dump all their extra power somewhere and wind power is strongest at night, but solar is the opposite, as you mention.

As for the WSJ article, I agree that the general public is not yet informed about EV ownership and its quirks. That is to be expected when EVs make up 3% of cars on the road at this point. They are still in the early adopter phase. Anyone purchasing an EV does need to educate themselves about some of the do’s and don’ts. There are plenty of DC fast chargers across the country on all the major interstate routes, so there are few excuses for having to use a puny Level 2 charger on a road trip except for overnight at your hotel. The women in the story would have saved hours’ worth of their time sticking to only DC fast chargers along their route. If you want to drive off of interstates, road trips will be very slow and difficult in EVs. The EV6 they drove is the fastest charging EV you can buy right now (or close to it) and can charge from 10-80% in just 18 minutes, so basically every 200 miles or so you stop for 18 minutes. That is much more time than gas, but not the hours they talk about in the article.

Here is the Electrify America network map for DC fast chargers:

Here is Tesla’s supercharger network map for its DC fast chargers:

Regarding their running out of charge, car manufacturers are very bad at designing range estimators for their cars. They do not adapt well to changes in terrain, wind, rain, temperature, and speed, so they are often referred to as “guess-o-meters” by the EV community. That is definitely a barrier to widespread adoption. They are working on improving these estimators and Tesla does a very good job with their navigation system, which will map out all the DC fast chargers along your route for you and tell you what charge you will get there with, how much time you will spend charging, and how much you need to charge to reach your next destination. They are the only manufacturer currently using this helpful feature. Tesla does use an algorithm that accounts for efficiency changes due to speed and elevation, so its range estimates tend to be more accurate than most.

Driving an EV on a road trip right now requires additional planning that these two women did not appear to do. You need to map out your route using an app like A Better Route Planner or at least look at the Electrify America map before your trip and know where you need to charge before you need it so you don’t run out of juice. You shouldn’t go below 10% power as well, to avoid running out while you look for a charger. Level 2 charging should only be a last resort, as it is painfully slow for a road trip.

Regarding the spaceship comment: most EVs come loaded with high tech gadgets to offset their higher costs and because they are marketed as futuristic vehicles. Thus, those averse to learning new technologies and interfaces and door handle types should avoid them for the near future.

I forgot to include links to the DC fast charger maps

https://www.electrifyamerica.com/locate-charger/

https://www.tesla.com/supercharger