About two weeks ago, New England got a punch in the mouth from old man winter. I tuned into the Mt. Washington Observatory (New Hampshire) to check the conditions. On Friday evening, February 3, it was cool and breezy at minus 46°F[1] with 99 mph wind and freezing fog. I dig that.

Today’s post continues last week’s discussion on wholesale electricity markets, including capacity and energy-only markets. Summary of that post:

- Wholesale markets are headed for trouble because

- Electricity cannot and will not be stored in bulk quantities

- Society cannot function without electricity

- Grid loads are getting spikier, and that does not align with half-random, half-cyclical renewable electricity generation

- Descriptions of capacity and energy-only markets

The two primary reasons wholesale competition is not working, lack of storage and the necessity of the commodity, lead to market manipulations that must be headed off in many ways. And therefore, the “competitive” markets are increasingly looking like versions of vertically integrated utilities that own everything from the pile of coal to the customer meter. See last week’s discussion regarding Texas, for example.

“Competition” and Electricity Prices

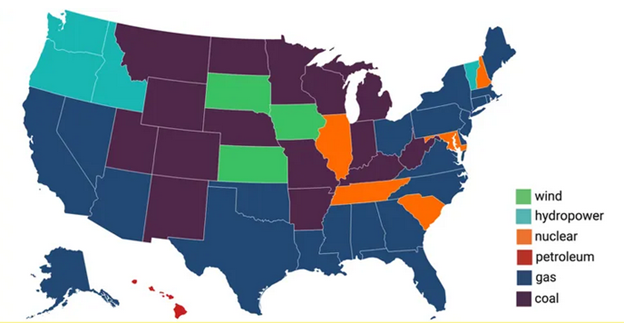

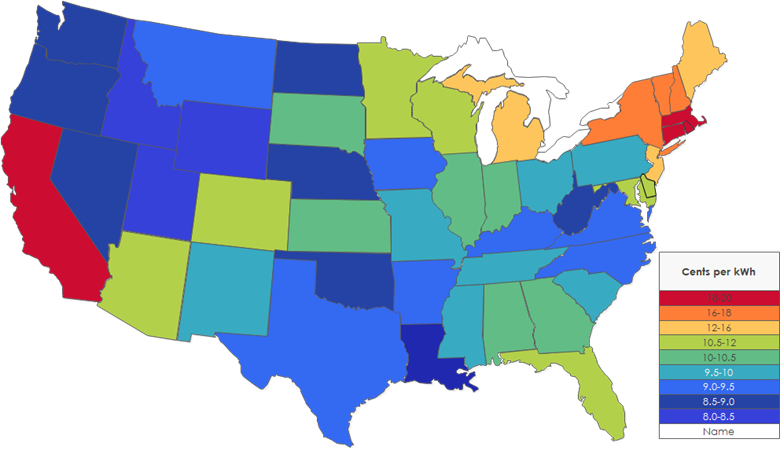

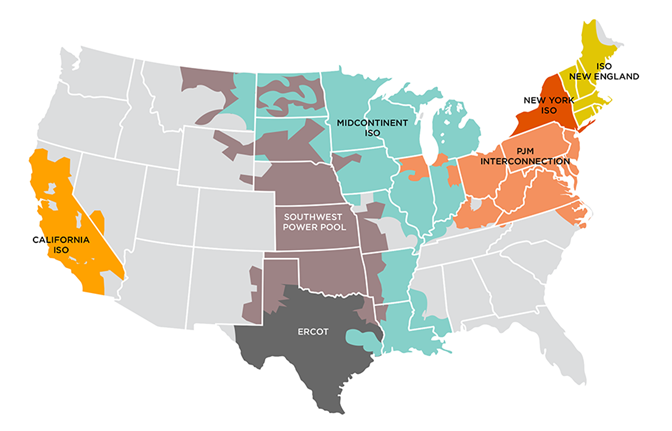

The Wholesale Electricity Markets paper published by The American Public Power Association states, “In fact, retail electricity prices are, on average, higher in RTO regions, and there is scant evidence that this price differential has produced greater levels of reliability or significant infrastructure development.” Is that true? Let’s look at state prices in the lower 48 and compare them with the ISO/RTO map[2].

The yellow to red states have very high electricity costs compared to the rest of the nation. Those are shown in two-cent increments. The average retail price for 38 states is less than 12 cents per kWh, and the average price for 25 states is less than 10 cents per kWh. Indeed, regions with competitive wholesale markets do not have lower prices, but exceptions exist.

What about fuel type? It’s as clear as mud with one exception: hydro from depression-era projects is the cheapest. Look at the price differentials within markets like MISO or PJM – huge differentials within the same wholesale market. Why is that?

What about fuel type? It’s as clear as mud with one exception: hydro from depression-era projects is the cheapest. Look at the price differentials within markets like MISO or PJM – huge differentials within the same wholesale market. Why is that?

Capacity Auctions v Cattle Auctions

MISO, PJM, ISO NY, and ISO New England have capacity auctions, but a capacity auction in the electricity market is not like an auction for cattle or cars. First, wholesale electricity markets are reverse auctions where the last kW is provided at the lowest cost the last seller is willing to take. Everyone with offer prices below that gets the same price.

A rancher doesn’t need to sell cattle at a price he doesn’t like. He can keep them, maybe until next week, or find some other auction barn on a better day. Furthermore, his cattle may be superior to the neighbor’s cattle. Electricity is a tasteless, odorless, invisible commodity of 100.00% sameness that cannot be kept for sale another day.

Generation Stack

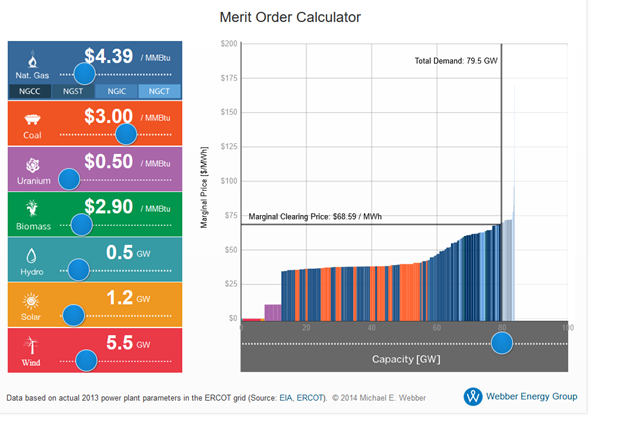

I found the following cool toy from Weber Energy Group for ERCOT/Texas. Some people like video games, while Jeff is fascinated by an interactive generation stack model. Weber calls it the merit order, and others call it a generation stack.

Notice that there are four types of natural gas plants: combined cycle, steam, internal combustion engine, and combustion turbine. The differences are beyond the scope of this post, other than I will say that combined cycle is far more efficient than the others – like 50-60% versus 20-30%.

By the way, ERCOT’s (Texas) peak demand is about 80 GW, so that part below is accurate.

Texas doesn’t have a capacity auction, but a resource stack in a capacity auction might look similar. Whether it’s capacity or electricity, every generator that bids less than the clearing price gets the clearing price. Wind, hydro, and nuclear are always price takers, meaning they bid zero and take whatever the clearing price is. Does this work for cattle? No.

Bilateral Contracts

Within these wholesale markets are long-term power purchase agreements between generators, say, a wind farm owned by Duke Energy in Iowa, and the local distribution companies (LDC), known as load-serving entities (LSE), also known as utilities in Iowa. Although wind farm owners are price takers, natural gas plant owners are not. The owner of a plant with a long-term power purchase agreement with an LSE wants to clear the auction, so they get something for their capacity. If they don’t clear, they get nothing and pay twice for capacity – once for the plant they already built and again for the auction clearing price. Confused? Good, because it’s decidedly confusing!

As an investor considering entering the wholesale capacity market, it seems like a poker game. I can bid into a “forward capacity market” good for three years, but my hunk of steel is good for 30 or even 60 years. How does it feel as an investor considering whether to build a baseload power plant in a market based on a poker game? Risky. I’ll put my money elsewhere. See how it works?

Consider that the LSE may have a contract with a 500 MW generator to deliver electricity for five cents per kWh plus fuel for 30 years. That price differs from the wholesale market’s price(s) 99.9% of the time. It doesn’t matter. They pay the clearing price and settle the difference with a “contract for differences.[3]” So how is this competition?

Transition

I’m working my way toward a mind-boggling conclusion for this year’s lessons in wholesale markets. Will we conclude next week? Are you boggled yet?

[1] Tied February record low set in 1943. One degree from the all-time low set in January 1934.

[2] Average retail price of electricity, all sectors, 2021. https://www.eia.gov/electricity/sales_revenue_price/

[3] https://www.publicpower.org/policy/wholesale-electricity-markets-and-regional-transmission-organizations-0