In many states that are relatively new to energy efficiency, legislators often cave to large energy users and allow them to opt out of programs because hey, they use a ton of energy and therefore, OBVIOUSLY to any moron, they control and manage these costs as well as any dunce could. Why should they throw money at a program that won’t help them?

Come to think of it, programs available to these large users in many places are dysfunctional, poorly conceived, and not thought through from the perspective of the customer, so I can see their point to some extent. I already have a type of colossal program failure that has been proven to produce nothing in many jurisdictions and I’ll talk about that next week or some other time.

The only real reason for large users opting out is that they think they can better spend the relatively tiny bit of money they would contribute to the program or more likely, they’d rather not pay anything and continue with business as usual. Both are foolish.

Let’s just use an example of a large user with $10 million in energy costs, paying 1% to the EE fund, which is $100,000. This sounds like a lot of money. It is not for a company of this size.

Allow me to demonstrate how foolish opting out is, using a rule of thumb that program incentives typically equal one year’s energy savings at minimum (I have seen incentives as high as FOUR year’s savings, in which case a psychiatric evaluation should be ordered up for opt-outs). Companies that opt out generally have to meet the savings goals the utility needs to meet in return for opting out, and this too, is generally in the region of 1% of sales, or in the case of the customer, 1% of consumption.

Take an opt-out and opt-in comparison for the above $10 million customer for a $200,000 project with $100,000 savings. ASSUMING no difference in customer time (time is money) and expense[1], the ROI is exactly the same. The opt-in customer pays $100k to the EE pot and gets it all back as an incentive for doing the project. However, the reporting for the opt-out customer will take at least $10k, I would guess, if they do a decent job.

Now suppose the investment is doubled to $400,000. The opt-in customer still only pays $100k into the program but gets $200k back in incentives. The customer starts to take other peoples’ money as he implements larger projects. Suddenly, the ROI starts quickly rising above the opt-out scenario.

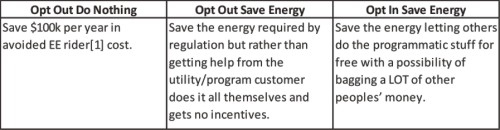

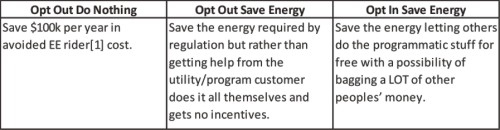

The only way the opt-out customer comes out ahead is if they plan to do nothing, in which case, rather than paying $100k into the EE pot, they pay nothing, all else equal. So, the scenarios become (see table to the left):

The “opt-out do nothing” scenario cannot stand, because customers agree to meet their goals, and this too, is where the BS continues. The typical opt-out customer includes manufacturers. Efficiency to manufacturers many times means high output and no shutdowns – not low energy use per unit of production – aka, ENERGY efficiency. Due to the lack of EE expertise beyond lighting, we see many doozers when evaluating projects from customers that opt out.

To use one example I used before (company name and project totally made up to protect the guilty), a baseball bat manufacturer switches from manufacturing wooden bats to aluminum bats. Wood requires the operation of a large kiln for drying, lathes, lacquer and all this sort of stuff. Making aluminum bats allows them to shut down the kiln, turn off the lathes, lay off half the workers, close half the facility, and increase production. The energy consumption per bat decreases. Problem: this is a totally different manufacturing process. The baseline is not the manufacture of wooden bats. The baseline is standard practice for making aluminum bats. What is that? At the point of evaluation, they don’t know. No alternatives were explored when they switched. There are no savings here. What a mess.

Another one includes a “behavioral” change where instead of running shifts every day of the week, the customer switches to running around the clock fewer days, primarily due to long wait times to start up and shut down every day, wasting energy and labor. Programs are not meant to incentivize avoidance of obvious absurdities. We probably don’t have the whole story, which may include going from 24/7 operation to 24/4 operation. No, reducing production is not energy efficiency.

Smart large users opt in and leverage the program for all it’s worth. Even the hugest, most goal-driven companies saving dozens of megawatts (no kidding) leverage programs to the max. Somebody has to save energy and demand and it may as well be me, large user. I take money paid from my less intelligent competitors and other citizens; my utility loves me because I am making giant steps toward their mandated goals; my colleagues in other parts of the country are envious; my CEO loves me because I’m substantially adding to the bottom line and reducing risk; and I take a huge administrative/management burden off my plate and give it to the program/utility.

If this is not a competitive advantage, I don’t know what is.

[1] Opt-out customers must file their own plans and reports just like the larger utility program and that takes substantial time to do any sort of reasonably acceptable job.

[2] A rider is an added fee, usually per unit energy used for energy efficiency, fuel cost adjustments and other things.