R Value Costs, Climate Specificity, and Why Business Outcomes Matter

In this week’s unusual Rant, I am stepping back to take a hard look at standard energy-efficiency upgrades and tips that circulate endlessly across the internet, conference slides, and contractor recommendations. Many of these ideas are well-intentioned, some are genuinely effective, and others quietly fall apart once cost, climate, and fundamental physics are factored in. Rather than arguing from theory, I will walk through a handful of familiar measures using real buildings, real constraints, and the simple question that often gets skipped: Does this actually make sense?

Air Sealing And Weatherstripping

This one is a no-brainer, but hard to measure on the utility bill. A few years back, I sealed my rim joists with spray foam insulation, which adds some insulation but more effectively reduces infiltration, mainly due to the stack effect (more below). Figure 1 shows one rim-joist cavity plastered with urethane foam, insulating the cavity and sealing penetrations to the outdoors. Penetrations include ductless heat pump refrigerant piping, power, and a water spigot.

Figure 1 Spray Foam Rim Joist

Stack Effect

The stack effect occurs due to differences in air density between indoors and outdoors. As mentioned last week, warm air rises and cold air falls along a cold vertical plate, like frost on a hotel room window. More effectively, when air is contained in a channel, it can generate some strong buoyancy forces that move a lot of air. You’ve seen the classic nuclear power plant cooling towers. There are no fans; only natural convection driven by buoyancy from temperature and the proportional difference in air density. Buildings, especially tall ones, can generate similar forces.

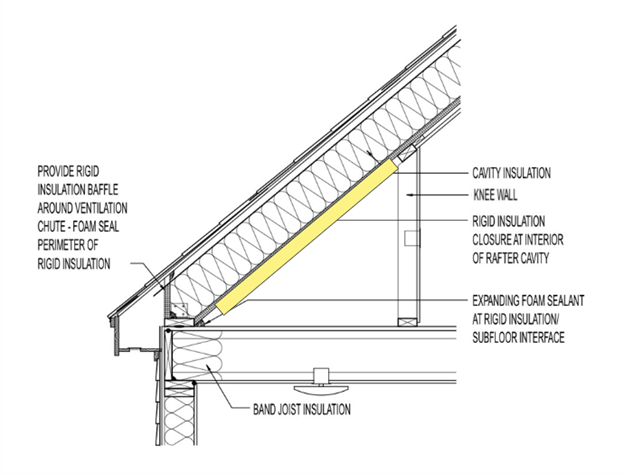

Figure 2 shows how air density changes with temperature, all else equal. With almost zero flow resistance, such as an open window with a screen, a substantial flow can be generated with just a 10-degree indoor-to-outdoor temperature difference at a single floor elevation, as in a single-family home. This makes sleeping downstairs on a cool summer night comfortable, while the upstairs doesn’t cool at all.

Figure 2 Air Density and Stack Effect

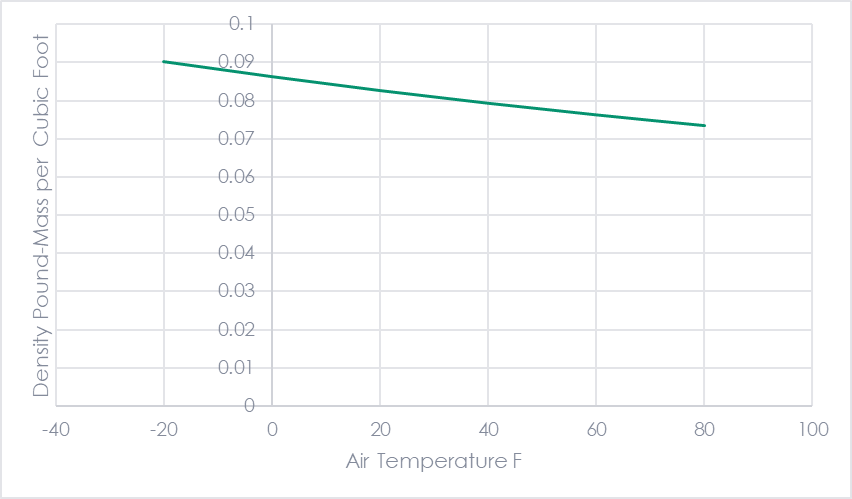

Tall commercial buildings, such as the Chicago Marriott Downtown, can generate a powerful buoyancy force, which can result in the arctic blast I described last week. I like the stack effect cartoon shown in Figure 3, courtesy of Henderson Engineers. To make matters worse, commercial buildings often include substantial exhaust from restrooms and kitchens, with inadequate makeup air balancing. The result: wind tunnels at the martini bar, and a locomotive is needed to pull the door open.

Figure 3 Stack Effect Cartoon

The bottom line: building owners and operators may not care much about the utility bill or trying to control the climate or weather, but they will care if dollars from their core business, like martini sales, fly out the door or through the roof. Advice for energy auditors: solve business problems that just so happen to save energy.

Duct Sealing

Thirteen years ago, I took aim at HVAC duct sealing in cold-climate homes. The alarming claim that only half of furnace heat reaches living spaces ignores basic thermodynamics when ducts are located inside the conditioned building volume, as they typically are in the Midwest and other cold climates. Heat that leaks from ducts in basements and other conditioned spaces is not lost to the outdoors. It remains within the control volume and offsets building heat loss. Duct sealing only produces meaningful loss reductions when ductwork runs through unconditioned attics or crawl spaces, and that is often in warmer climates like California, where granted, cooling losses can be significant. The bottom line: think big picture before counting the energy-saving chicks.

Insulation

Two things matter for adding insulation to attics, walls, or window replacements: 1) the initial insulating value and 2) the cost per added R-value (described last week).

Wall Insulation

Insulation ROI follows the 1/x rule, where x is the starting insulation level. If the R-value is small, heat loss or gain may be substantial. For example, an uninsulated wall may have a composite R-value of 5. That’s a good starting point for a cost-effective insulation job. However, what’s the cost to jam insulation into that wall cavity? It depends on the exterior finish.

- Vinyl siding is one of the easier exteriors to work with for retrofitting insulation. It can be popped off and back on with minimal damage, keeping installation and restoration costs lower.

- Wood or composite siding is a bit more difficult. Panels require careful removal and precise reattachment to prevent warping and cracking.

- And then there is my home construction: thick, brittle, chunky, and expensive-to-blend stucco.

Homeguide.com provides a nice overview of pricing differentials for various applications. They show that insulation itself runs in a tight cost band of roughly $1.00 to $2.50 per square foot, but, as I alluded, labor costs vary tremendously, up to 10x from low to high. The total cost ranges from roughly $1.50 to $7.50 per square foot, up to $8,500 for a typical home. To be “safe,” I’d add 50% to these rule-of-thumb estimates.

I once asked an insulation contractor for an approach to insulating my home with thick stucco siding on the outside and thick cement plaster over wire mesh on the inside. He suggested going at it from the inside. I said, uh, no. That would be a huge pain in the keister to segment and contain the dust from room to room. It would cost a fortune and pay for itself in never-never land dog years.

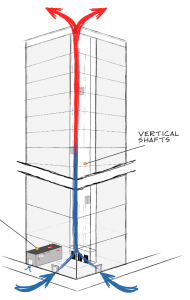

Roof and Attic Insulation

Roof and attic insulation has similar divergent cost challenges. Blowing insulation into an attic space is dirt cheap. Pile it deep. However, other types aren’t as easy to insulate, such as the knee-wall construction, which is common in my neighborhood. See Figure 4. I have no idea what the infatuation was with wasted floor space, but that’s what knee wall construction does, as shown in my rendition from a few years ago, repasted in Figure 1. To the right of the knee wall is the occupied space. The only way to add insulation there is on the roof deck, from the outside. I suggested that when I reroofed, but the contractor looked at me like my head had just spun 360 degrees. That was not standard practice, and I could tell that whatever the normal price was, he would add a zero to the end. Never mind.

Figure 4 Knee-Wall Construction

Windows

Circling back to replacing windows, especially the ones that suck heat like an ice wall described last week, replacement costs for homes average roughly $900 per window, or roughly $35-$40 per square foot.

Well, as I noted above before doing the calculations on my window replacements, add 50% or in my case, 100%. My cost per window replaced was $2,300 each, and the cost per square foot was $112[1]. Booyah.

Was it worth it? I can see through and operate them easily (remove screens and wash them). Does that count, along with less energy waste and a more comfortable feel? To me, yes, but I’m irrational, for sure. And hey, it’s not like bellying up to an iceberg.

Next Up

Next week, I will continue my journey down OpenAI energy efficiency alley, adding stiff shots of reality along the way.

[1] Standard double pain, double hung, argon insulated, low-E, etc., Pella Windows