I spent a few days farming last week, resulting in a lot of podcast time. A couple of them provided kindling for this Energy Rant or two. The first noteworthy podcast included an interview with David Sacks, Chair of the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. He was interviewed with David Horwitz and Marc Andreeson on their a16z podcast.

Gates Surrenders

There’s a cornucopia of interesting stuff in the podcast, so I suggest you check it out. Point one is that Sacks thinks AI doomerism will go the way of climate doomerism, which itself provides plenty of fodder for a Rant post. You may have read or heard that Bill Gates has declared defeat in his scrawny-arm-wrasslin battle with climate change. The Wall Street Journal quotes him, “It’s [the climate change battle] diverting resources from the most effective things we should be doing to improve life in a warming world.”

Bill Gates has a unitary interest: Bill Gates. Do not think otherwise. Here is another excerpt: “His 2021 book has the nuanced title, ‘How to Avoid a Climate Disaster.’ Without innovation, he wrote, ‘we cannot keep the earth livable.’ The effect on humans ‘will in all likelihood be catastrophic.’”

What happened to the world champion technology grifter? Hmmm. Artificial intelligence. He and others need energy by any means to power AI data centers. In another podcast, I heard that the tech broligarchs (Zuck, Cook, Bezos, Pichai, Musk, Altman, and of course, Bill Gates, et al.) will burn coal, leaves, or trash to power their data centers. I would add that they would burn used tires, hospital waste, PCB-laced transformer oil, plastic straws, railroad ties, Styrofoam peanuts, and their mothers’ retirement savings buried in the backyard – whatever is necessary to keep the data centers running.

If It Doesn’t Move, Subsidize It

There is a lot to unpack, but I’ll get back on course. Sacks used an oldie but a goodie from Ronald Reagan, circa 1986, “If it moves, tax it. If it keeps moving, regulate it. And if it stops moving, subsidize it.”

I would say The Gipper or his speech writer should have revised that a little to say instead, “If it moves, tax it. If it keeps moving, regulate it. If it doesn’t move, subsidize it.”

There I was – in the epicenter of subsidized energy that would otherwise not be moving. First, there is corn, which is used to produce ethanol, a process that was heavily subsidized from 1980 through 2011, as shown in Figure 1, in constant 2024 dollars.

Figure 1 U.S. Corn Ethanol Consumption and Subsidies, 1980-2011

Subsidy sources:

- 1979–1982: $0.40/gal ethanol (Energy Tax Act 1978; raised to $0.50 in early 1983). Policy Perspectives

- 1983–1989: $0.50/gal (STAA 1982). Renewable Fuels Association

- 1990–2004: effective $0.54/gal ethanol via the gasohol excise exemption (5.4¢/gal of E10). Vermont Law and Graduate School

- 2005–2008: VEETC $0.51/gal (American Jobs Creation Act 2004). Every CRS Report

- 2009–2011: VEETC $0.45/gal (2008 Farm Bill) until expiration 12/31/2011. Taxpayer

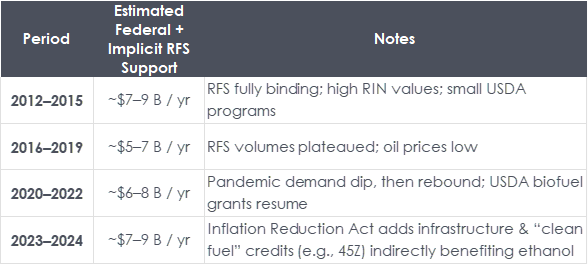

After 2011, our betters in DC switched from an outright cash incentive to a force-fed RFS (Renewable Fuel Standard). This was a backdoor subsidy, summarized in Figure 2. Essentially, the subsidies are worth approximately $1 per bushel of corn produced in the United States.

Figure 2 RFS Implicit Subsidies

Corn Production Blowout

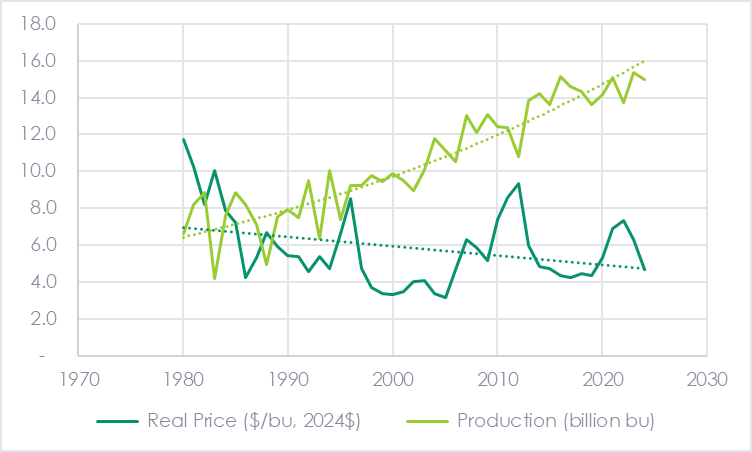

One result of the subsidies is that corn production accelerated like crazy, depressing long-term prices. However, farmers have also become incredibly proficient at growing crops, with little gain in real prices, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 U.S. Corn Production and Price per Bushel in 2024 Dollars

Sources:

- USDA ERS – Feed Grains Database (average farm price received for corn, nominal $/bu)

- USDA NASS – Crop Production Annual Summary (U.S. total corn production, billion bushels)

- BLS – CPI-U Annual Averages (1982–84 = 100) for inflation adjustment to 2024 $

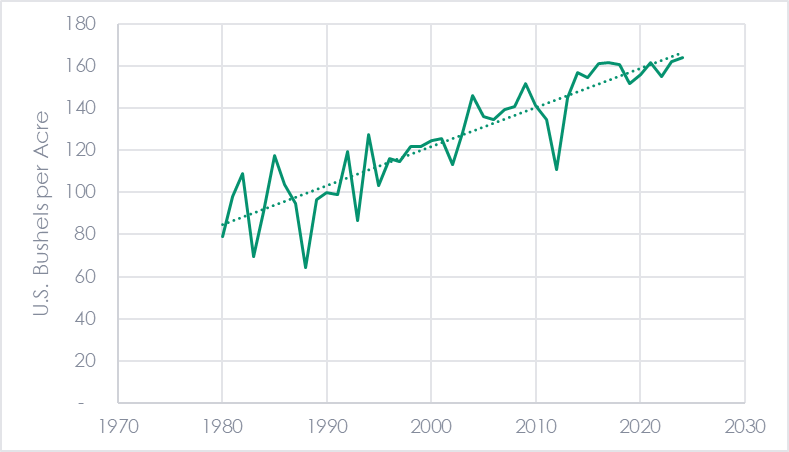

Figure 4 Productivity, Bushels per Acre

Corn production increased 160% and productivity doubled in barely 40 years of my life. How are farmers achieving this blowout success? From my perspective, drainage is a significant factor. If you’ve ever tried to grow tomatoes in a bucket with no drainage, you know what I mean. The soil is waterlogged or concrete when dry. Roots need oxygen, and the microbes that generate plant food in the soil thrive in aerated soil, all of which is unleashed with millions of acres of injected drainage tile. The soil heats up faster in the spring, allowing seeds to germinate quickly and shoot out of the ground fast. Compaction is reduced. It’s sustainable. Less fertilizer is needed as nature takes over. Now, if only I knew how to treat my potted plants the same way. ?

Storage Evolutions Can’t Keep Up with Productivity

Over the years, grain storage infrastructure has evolved and grown in spurts, but has never kept up. First, there were wooden grain elevators in every town – the type that were prone to explode due to grain dust. These were a lumber industry’s dream because the walls were made of laminated 2x6s stacked – like how many stacked dollar bills does it take to reach the moon? These were prominent in the 1930s and before but were still in use in the 1980s, at least. A few still exist, but they’re so tiny their storage capacity is irrelevant.

Figure 5 Wooden Grain Elevator

Then they transitioned to concrete silos, like the classic Bunge or Cargill facilities shown in Figure 5. You’ll see these along rail lines and rivers for obvious reasons. Like the lumber company’s dream, these were concrete companies’ dreams. How did they pour concrete a couple hundred feet in the air? Probably with cranes in small batches, I’d guess. In a few decades, demand for storage blew past these much-larger facilities’ capacity to store productive farmers’ fruits.

Figure 6 Concrete Grain Silos

In the 1980s and 1990s, elevators became more cost, and consequently, environmentally conscious. They transitioned to building massive steel bins – bins, not silos! Figure 6 is a photo of a large steel-bin facility in Beltrami, MinneSOta.

Figure 7 Steel Bin Grain Elevator

That technique lasted for a decade or two, and now what are farmers and cooperatives doing? Just piling it on the ground! You don’t need AI to size up the corn mountain next to the old concrete silos in Figure 7.

- I estimate the mountain to be roughly 4 million bushels compared to about 1.3 million bushels in all the concrete silos combined. You must be a paid subscriber to get the secret math behind that.

- One semi-trailer can legally haul about 1,000 bushels over the road.

- That’s 20,000 acres, or about 31 square miles (5.6 miles squared), of corn at 200 bu/acre. I’m in!

- Back in 2016, it was estimated that Iowa alone had 600 million bushels piled outside. Iowa has 100 counties. Now I’m even more in! Nerd out!

Figure 8 Bunge Corn Mountain

The upshot: productivity is through the roof, prices show a long-term decline, and climate change, if anything, has boosted production. I chatted with my mom during the trip, and we reminisced about the miserable, wet, and freezing harvests of days gone by. One year in the late 1970s, we ran through the nights while the mud was frozen. During my freshman year in college, a massive snowstorm struck in late October, and the snow persisted through the entire winter, never melting. The first dozen or so rows of every field served as a snow fence. In recent years, it’s creampuff city with sunny 50-degree weather. There hasn’t been a wet, crappy, cold fall for thirty years.

Next week, I’ll wrap in food and cross-contaminating energy policy.