It may be that I pay more attention compared to several years ago, but there seems to be a lot of churn in energy efficiency policy today. Some states, particularly those with a short track record in efficiency, are getting squeamish or have backed off. These include Indiana, Ohio, Missouri, and Michigan. With excess capacity, we have utilities, and in some cases their political (money) support against intervenors, and that is a fairly weak position for efficiency in some states, including some of those just listed. There is nothing better for our industry than the need to build power plants in someone’s backyard. That will turn voter support for efficiency!

Overwhelmingly, a politician’s number one concern is numero uno, as we used to say. That is, stay in power above all else. Very rare is the bird who is willing to lay down his political life for what he stands for.

Broadly, it boils down to voters’ organic position on the issues versus corporate political support, which buys ads or other media to influence the low-information lemmings, er I mean, voters.

In other states, there is strong organic political support for energy efficiency. You can see these on the recently referenced ACEEE State Score Card. High ranking states have strong support of voters. One of these, of course, is California where they have the “metal to the pedal and the thing to the floor”[1].

Earlier this fall, the California[2] legislature passed senate bill 350 which calls for 50% reduction in petroleum use, a 50% increase in building efficiency, 50% renewables by 2030. It is dubbed 50/50/50. Why not 50505030? Or E-I-E-I-O?

The bill seems to have some good stuff in it like directing the CPUC to achieve greater efficiencies in buildings that fall far below current energy codes. For single-family homes in the state, this is a big opportunity as noted in Home Runs in Residential HVAC, published just before the law was passed. Coincidence?

The other thing, noted in the linked articles above, is the law includes a “paradigm shift” in the way efficiency is measured: “energy efficiency savings and demand reduction reported for the purposes of achieving the targets established pursuant to paragraph (1) shall be measured taking into consideration the overall reduction in normalized metered electricity and natural gas consumption where these measurement techniques are feasible [my emphasis] and cost effective.” …” Rather than rely on a series of ex-post studies, including a stack of regulation that includes considerations for energy code and attempts to account for “free ridership” and other subjective impacts.”

Wow – there is a lot to chew on in those few words. First consider the part I emphasized. What does feasible mean? According to my dictionary:

Measurement of savings at the utility meter is always feasible according to this dictionary – always feasible but never correct without a lot more analysis. Short of something major like a rooftop solar system, energy savings from efficiency measures will never be accurately determined at the residential meter level. For widget programs like lighting, HVAC, or appliances, large scale studies are required to accurately capture the impacts. You can’t see these things at the meter.

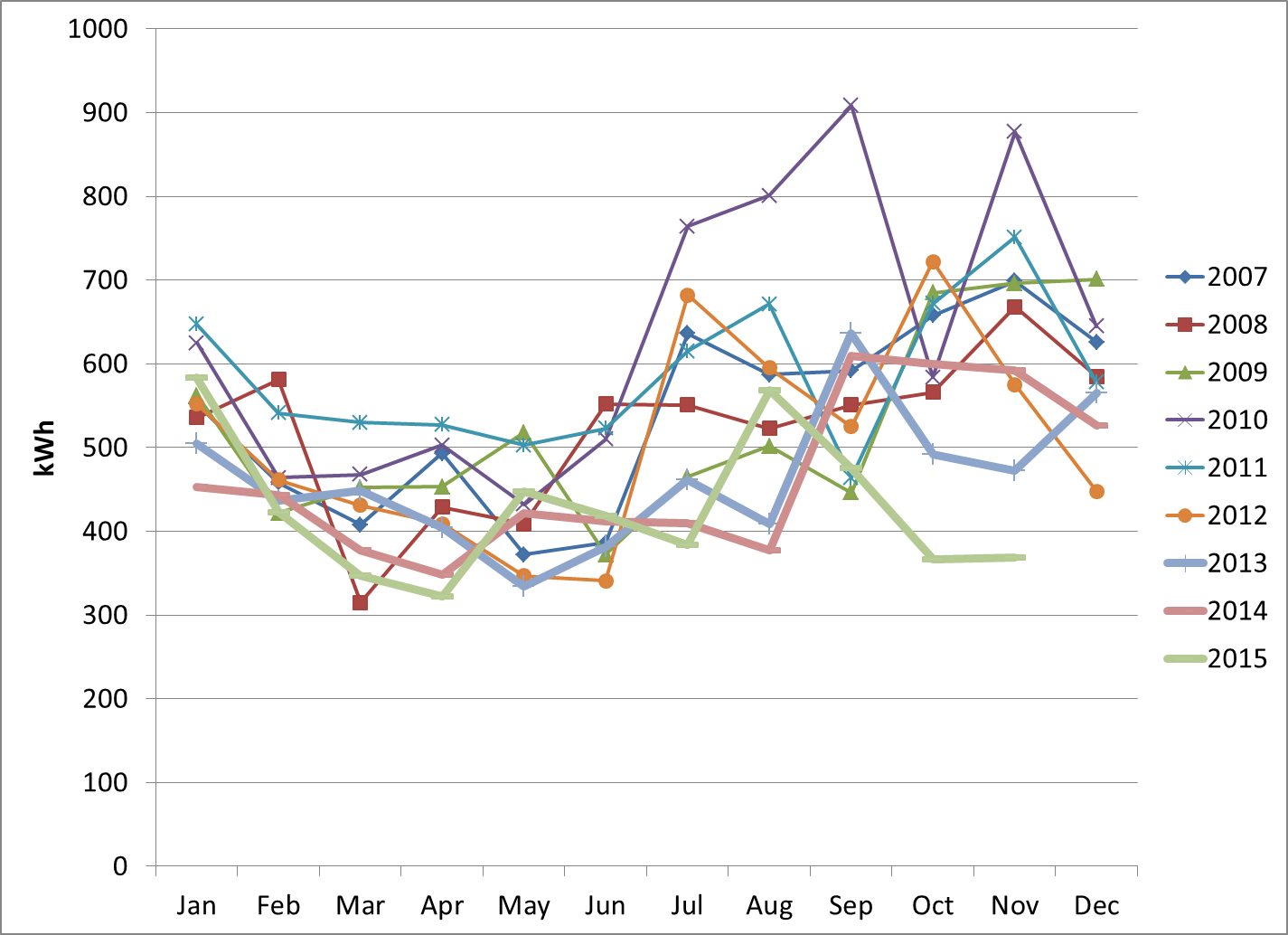

Behold, as a helpless energy nerd, I track my monthly consumption by hand, shown below. Notice any trends? What was going on in 2010? I don’t know. And I live here. It was fairly hot, but not as hot as 2012.

Three things dominate my variable electric use: dehumidifier, central air conditioning, and the clothes dryer. In May of 2013, the conventional wash machine and electric dryer were replaced with a high efficiency machine and gas-fired dryer. To make it a little easier on the eyes, I thickened the use curves for the post-gas-dryer periods. I used to run the dehumidifier more in the fall to dry firewood in the basement. This year, to make it easier on myself, I shifted it to the spring (don’t ask).

The punchline is, we can forget about accurately assessing savings for typical measures at the typical home’s meter. There is too much noise.

For some residential programs/measures such as weatherization, a billing regression (curve fit) is the only way to estimate savings. The only benefit of a site visit is verification that something actually happened to save energy. Regression analysis here should include participants and non-participants (control group). The non-participant data are used to filter out effects of everything not related to the measure such as weather, an economic upturn or downturn, etc.

As for commercial and industrial, I have seen too many impact evaluations that take a blinders view of billing analysis and don’t normalize for anything – they don’t filter for other major factors that affect energy consumption like weather, occupancy, number of shifts, and production levels.

The only reasonable way to use meter data is to develop a regression model that accounts for those things mentioned previously. Only the most progressive portfolios are beginning to use energy information systems to do this regression. In other words, a whole lot more – more than smart meters, more than energy dashboards, and more than wizzbang doohickeys needs to be developed before we reach this Graceland.

[1] A quote from Sally Field’s character in Smokey and the Bandit, one of my favorite childhood movies.

[2] Hang with me. The rest is universal, not just about CA.

Join the discussion One Comment