Last week, I was reviewing a scope of work for retro-commissioning, also cleverly known as RCx – and it moved me to pulling hair out by the fistful. “That’s it”, I thought. “I’m going to relieve my rage on next week’s Energy Rant.”

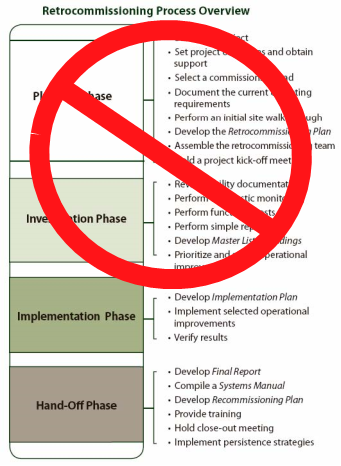

First, there is the infamous flow/process chart for completing an RCx project. As you may infer, I am not fond of the “Planning Phase”. In fact, it seems this process was developed by a program implementer for the program implementer (to spend more time and thus make more money while achieving little more than wasting time).

Retro-commissioning has many great benefits including fixing problems that improve comfort, lower maintenance cost and associated labor – and of course, energy savings, all with a return that would thrash the Alibaba’s initial public offering.

Even so, the number one ding against retro-commissioning is it takes a while; patience – not unlike I learned as a kid when I had to wait for Christmas to get toys. From the time we got the catalogs in August, I could only ogle over potential toys – my favorite of which was the slotted electric racetracks. Any time other than Christmas, I might have been able to pry a dollar from my mother for a Hot Wheel. The planning phase of RCx just adds to the excruciating wait. E.g., you can’t open presents till January 2nd, the day before the dreaded return to school.

Specifically, there are several elements of the planning phase that are a substantial waste of time and money.

- Set project objectives

- Document operating requirements

- Develop a Retro-commissioning plan

These sound pretty important, Jeff. They are, but at least to me, they are obvious.

- Objective: reduce operating cost, especially energy cost, and improve comfort as needed. Fix problems.

- Document operating requirements: maintain space conditions (or processes for manufacturers) within normal limits. This includes light levels, temperature, humidity and air quality.

- Develop a Retro-commissioning plan: Get to work.

Instead, we (Michaels) displace this planning-phase frufra with a screening phase, as in – is RCx right for this customer? The qualifiers are simple:

- Are there operational issues, problems, and/or deficiencies?

- Is the energy use higher than it should be?

- Is the customer interested, and do they have access to capital for implementation?

- Period.

The first two bullets for screening constitute the need for RCx. The third constitutes the desire and means to follow through. None of these are included in the ballyhooed Planning Phase above, although a walk-through to read the DNA of the facility and taking its vitals is typically very much worthwhile.

The other thing is: there is a big difference between retro-commissioning and commissioning. The big difference is the former project includes an operating history and the latter does not. You may be thinking, “duh”, but this deeply impacts the approach to these disparate services.

Referring back to that scope of work I mentioned above: One of the things that set me off, and would have resulted in my mouth getting washed out with soap as a kid, was essentially an RCx process to test building components and then fix them.

No. No. No. No. No.

Since the facility on the receiving end of the RCx has a track record, by definition any problems are already known and can be identified through discussions with customer stakeholders including occupants, facility staff, and management. Problem categories mentioned above include comfort, air quality, and maintenance issues. The other part, energy intensity, is a metric for the RCx service provider or program administrator to gage.

You may be thinking, “but there may be problems that the customer is not aware of.” Yes. What category do 90% of these fall into? The energy consumption category. Otherwise, if the customer has no complaints about comfort/maintenance, we don’t look for ways to spend money and drive up operating cost.

However, sometimes customers may tolerate things they shouldn’t be tolerating, and these things may need to be tweezed out of them during the site investigation and ongoing conversations. Another part of the 10% may include things like exhaust fan motors spinning away while the drive belt shredded a long time ago. Otherwise, if air is moving and the bathroom doesn’t smell like the last Flying J truck stop bathroom I used, it’s good to go.

Commissioning, on the other hand, includes new systems and/or a whole new building. There is no track record. There are no maintenance, comfort, and energy issues – yet. Here is where commissioning agents test, then fix per the findings of the testing.

Commissioning and RCx are similar in that both are used to fix problems, issues, deficiencies. A sound screening process for RCx to identify savings potential along with discussions with customer stakeholders and a visual inspection of systems and components is all that is required to get all issues on the table. The RCx agent needs to be adept at rooting out sources of waste, but this does not require blind carte blanche willy nilly testing of everything – that is a waste of time and money!