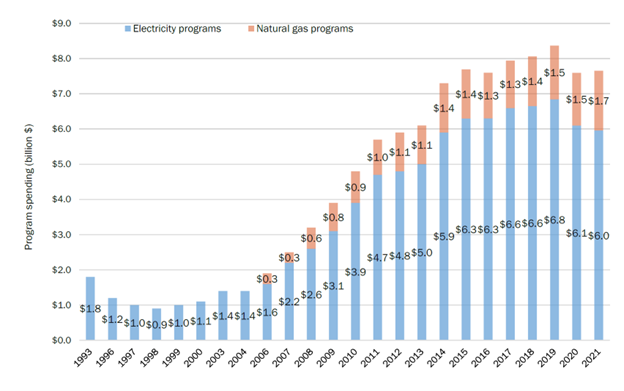

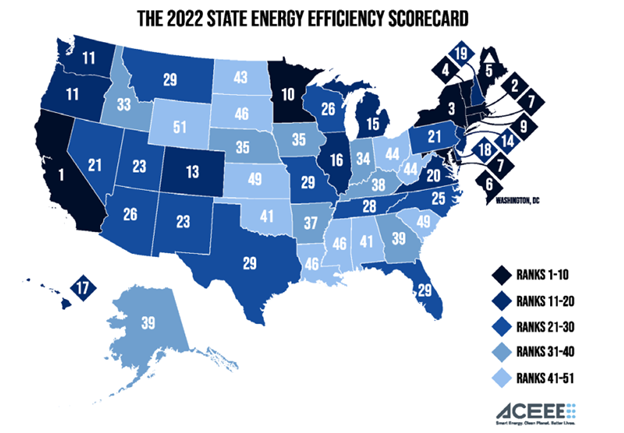

This week, we are continuing with 40 years of Michaels Energy and energy efficiency history, focusing on the years of growth. As alluded to in the last post, The Great Depression of energy efficiency hit in 1999, or to be a bit more precise, 1998. Data from the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy’s most recent state efficiency scorecard confirm my case.

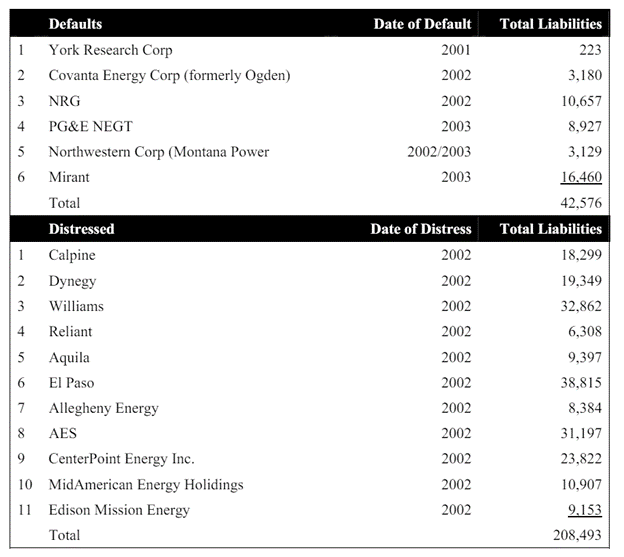

While The Great Depression of energy efficiency raged, utilities got caught up in the dot.com stock market bubble. They bought telecom companies, home security, resort properties, and power generation overseas. Those ventures ended poorly, taking some to the brink of bankruptcy. A table of failed and distressed utilities from this experiment is shown below. Like many failed ventures, companies rename and rebrand when restructured or emerge from bankruptcy. For example, in a three-way deal, Black Hills Energy grabbed electric and gas operations from Aquilla and Great Plains Energy in 2008.

While The Great Depression of energy efficiency raged, utilities got caught up in the dot.com stock market bubble. They bought telecom companies, home security, resort properties, and power generation overseas. Those ventures ended poorly, taking some to the brink of bankruptcy. A table of failed and distressed utilities from this experiment is shown below. Like many failed ventures, companies rename and rebrand when restructured or emerge from bankruptcy. For example, in a three-way deal, Black Hills Energy grabbed electric and gas operations from Aquilla and Great Plains Energy in 2008.

The Enron debacle ended in California utility bankruptcies and blackouts. Wildcatter utilities that flirted with or entered bankruptcy begged to return to the protections of a captive market in exchange for guaranteed stable revenue and earnings. Deregulation froze in place, and utility demand-side management (energy efficiency) programs started to grow again.

The Enron debacle ended in California utility bankruptcies and blackouts. Wildcatter utilities that flirted with or entered bankruptcy begged to return to the protections of a captive market in exchange for guaranteed stable revenue and earnings. Deregulation froze in place, and utility demand-side management (energy efficiency) programs started to grow again.

Birth of Third-Party Portfolios

As a result of the deregulation frenzy, Wisconsin decided to pull efficiency programs away from utilities and roll it all into a statewide program, Focus on Energy. It also required utilities to divest transmission lines and transfer them to American Transmission Company to avoid a “deregulation fiasco” like California endured.

Focus on Energy represented a giant vat of chum (money) that drew big fish (Sharks and Orcas). Lighting retrofits were the measure of choice that kept the chum lines rolling for years. At that point in our history, our comprehensive ASHRAE Level 3 assessments vacuumed up all significant energy-saving measures from window replacements to direct digital control systems, chiller plant upgrades, boiler economizers, and propane-air backup systems to apply for interruptible natural gas service. Lighting came along for the ride, like, yeah, whatever. As it turned out, the comprehensiveness was too big and slow to move without 50% buydowns from the Institutional Conservation Program, which was successful for us in our early years.

Twenty Years of Repeated Lighting Retrofits

The Sharks and Orcas ambushed the chum while we dawdled as sub-consultants on the evaluation side of the fence. That was a huge mistake for many reasons. First, lighting was highly scalable. Everyone understands it, and it’s highly visible, whereas the other stuff with significant impacts, like refrigeration and HVAC, is behind locked doors and above ceiling panels. Customers don’t understand those things. If you want to lose somebody, like describing a cadaver, carry on with your genius around HVAC controls at the next cocktail party. It’ll clear the room like a family of skunks, which I just saw waddling across a country road recently – charming, but you don’t want to be within earshot.

Second, lighting is excellent for energy and load reduction because most of it is energized during peak hours except for parking, street, and stadium lighting. My guess is that the lighting revolution of the last twenty years has been responsible for most of the zero-load growth.

Third, it’s easy to understand that anyone who can count and operate a calculator can analyze and sell lighting projects. It’s easy to retrofit and replace.

Fourth, it’s fast to retrofit and not invasive. Crews work nights and weekends; at worst, occupants notice nothing. Typically, retrofits enhance visibility and color rendering in the lighted space.

Fifth, it grows back. The first rounds of retrofits, dating back to my early days, were replacing T-12 lamps and magnetic ballasts with T-8 lamps and electronic ballasts. Next up was a high-bay frenzy, replacing technologies like high-pressure sodium and metal halide with T-8 lamps and electronic ballasts. Then came T-5 lamps and more efficient T-8 lamps. And finally, LED technologies. Socket lighting transitioned from incandescent to compact fluorescent to LED as well. Add it all up: there were probably 2.5 generations of lighting replacements and retrofits.

Custom Efficiency Beginnings

While our competition, the Sharks and the Orcas, scaled lighting portfolios that included sides and condiments of other technologies and program offerings, we were fortunate to grab and grow custom efficiency services and programs for our longest-running clients, Alliant Energy and Xcel Energy. Our days with these utilities date back to pre-1990s mergers working for their operating companies, Wisconsin Power and Light and Northern States Power. Over the past 10 to 15 years, we have rolled out spinoff programs under the custom umbrella, including commercial and industrial new construction, various flavors of retro-commissioning, and strategic energy management.

Portfolio Blowout

As shown in the ACEEE chart at the beginning of this post, mega efficiency portfolios exploded across the Great Lakes States around 2008-2009. They included Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. About five years later, Ohio and Indiana drastically cut their efficiency portfolios. Total spending on efficiency has been crabbing sideways since then.

I can’t help but look at state politics that drive energy efficiency. Efficiency programs have fared poorly in states that are now deep red, including Indiana and Ohio. Swing states like Pennsylvania and Wisconsin have tracked sideways for a decade or two. Blue states like Illinois and Minnesota maintain strong portfolios.

Next week, I will wrap up this series with the State of the Efficiency Union and a little forecasting of the coming decade.

Next week, I will wrap up this series with the State of the Efficiency Union and a little forecasting of the coming decade.