Google is still playing the carbon-free hall of mirrors, this time, claiming Gemini inquiries only result in 0.03 grams of carbon dioxide and five drops of water, less than Jalen Carter’s demonstration of contempt for Dak Prescott, the NFL’s highest-paid quarterback, who will never win a Super Bowl. (Lamar Jackson and Jalen Hurts, far superior quarterbacks, are far down the list at nine or ten on the salary list.)

Google’s claim is like measuring the CO2 emissions from a piston stroke from an on-site internal combustion engine used to power the data center. If you pick a tiny load, like a single Gemini inquiry, the number appears tiny, negligible, or microscopic. It’s the millions, billions, and trillions of inferences (and what about the training energy suck?) that add up to big numbers.

As of late July 2025, ChatGPT was clocking 2.5 billion prompts per day, almost exactly one trillion prompts per year, compared to 14 billion Google searches per day. Artificial intelligence is starting to gnaw away at search engines for e-commerce. I’ve never understood the algorithms behind Google searches, but I know number one in their minds: Google. Maximize revenue, baby, to the highest branded bidder that buys their products from a Chinese factory that sells the exact same product to a hundred different brands.

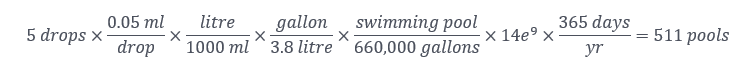

By the way, the 14 billion searches, even at a questionable five drops per search, roll up to 921,000 gallons per day, enough to fill 1.4 Olympic swimming pools, according to Alexa. That’s 336 million gallons or 511 swimming pools per year.

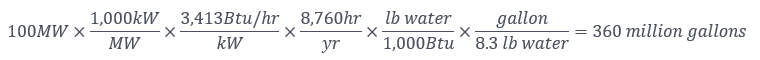

I’m not buying that. Looking at it another way, Figure 1 is an image of Google’s Council Bluffs, Iowa facility, shared in The Wall Street Journal article. The red boxes show humongous evaporative cooling towers; you can see the droplet plume on the WSJ photo. Assuming a 100 MW data center, a fairly small one for Google, my conservative math shows the following water consumption.

Voila, except this is a single data center, not all of Google’s data centers. Gemini even says “A 100 MW data center can consume between 760 million and 1.8 billion gallons of water per year, depending on its efficiency and the type of cooling system it uses.”

The drops per query or prompt are way off from my perspective – by orders of magnitude, sliced three different ways.

Figure 1 Google’s Council Bluffs, IA, Complex

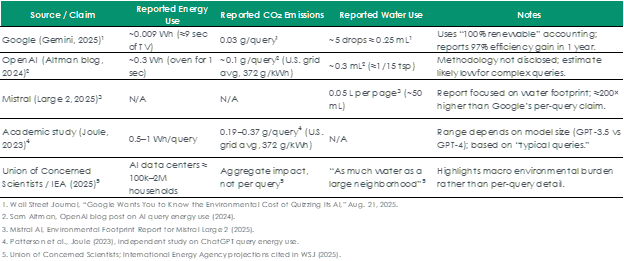

To true up Google’s spin, I sicced Sam on the case, and it produced the results and references in Table 1, which shows estimates of power and water consumption per prompt from numerous sources.

Table 1 Artificial Intelligencia’s Environmental Impact Comparison

Takeaways:

- Google’s figure (0.03 g/query) is 3–12× lower than most independent estimates.

- Water claims diverge even more: Google’s 0.25 mL vs Mistral’s ~50 mL per page (200× higher).

- Lack of methodological transparency (except partially from Google) makes these numbers easy to spin.

- Grid intensity matters: at 0.82 lb/kWh (372 g/kWh, U.S. eGRID 2022), all non-Google estimates are significantly higher than their PR numbers.

The Main Event – Merchant Power

Moving on to data center developers’ quest for power, they are building their own or striking deals with merchant power providers behind the utility meter, leaving balancing authorities (RTOs) and utilities to pick up the variable load.

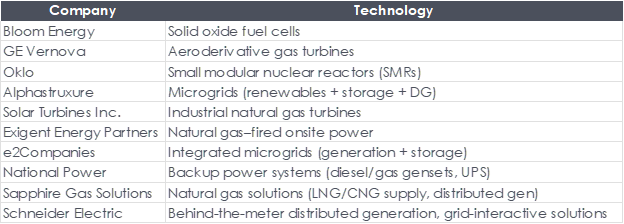

What sorts of generating assets are filling this void? Everything but coal piles and hydroelectric dams, so far. Table 2 includes a list of merchant power-generating companies represented at the relatively small Data Center Frontiers Conference that are bridging the gap left by the utility, regulatory, political, and bureaucratic complex.

Table 2 Merchant Generators Eating Utility Lunches Behind the Meter

Although the fuel cells are powered by hydrogen from unicorn flatulence, Oklo, whose CEO looks like that guy from the 3rd Third Rock from the Sun (Figure 2) has a future so bright, he’s gotta wear shades.

- Their representative at the conference said they have 14 GW of small modular reactors (SMRs) in their order pipeline

- Barron’s reports their stock price is up 1000% in the last year (as of a few weeks ago).

- The DOE has selected it to have three test reactors firing by next summer (that will be a test in speed)

These are huge expectations on a timeline. Good luck with that.

Figure 2 Oklo Third Rock

I wonder if any of the 14 GWs of orders are with utilities. Their reactors “are designed to run on nuclear waste and require refueling once every decade,” like some French fries, Miller Highlife, and a flux capacitor. For real, however, I can’t say how it works. Thirty years ago, I could, maybe.

Here’s what Sam tells me:

- Oklo’s technology uses fast fission, rather than water-moderated, thermal neutrons to fission U-235 atoms to generate heat.

- Fast fission reactors can squeeze more fission from spent fuel from conventional pressurized water (thermal neutron) reactors. As a result, they advertise free fuel and fuel recycling.

- Heat is absorbed and transported via liquid sodium, which doesn’t moderate neutrons. This allows the primary coolant loop to operate near atmospheric pressure.

- There is an intermediate loop to keep the radioactive primary coolant away from the steam generators.

- Steam generators make steam to spin a turbine in a conventional Rankine cycle power loop.

Sam notes that sodium reacts violently with water, which reminds me of hellion classmates of mine back in the 70s who got their kicks out of tossing sodium chunks in toilets to generate explosions. What could possibly go wrong in a power plant with a sodium-to-water heat exchanger?

The 16X jump (as of market close, 19SEP25) in OKLO’s stock price is unwarranted. Why? It’s generating electrons. They’re not AI electrons, super-intelligent electrons, or artisanal electrons from hand-made batches, like a fine bourbon. Hype, hype, with all your might! They are vanilla electrons like all the others, competing with electrons from every source, including unicorns and coal. Nevertheless, I wish Oklo the best of luck, as it may be a promising, scalable power solution behind the meter to circumvent the tectonic plate speed of the utility-regulatory complex.