This week, I dive into something I have wanted to know more about for some time: efficiency program funding mechanisms. This post is based on a recent paper released by ACEEE, Valuing Efficiency: A Review of Lost Revenue Adjustment Mechanisms.

Utilities must be allowed to make enough money to draw required investor capital, debt and equity, to fund their operations. Energy efficiency programs are funded by ratepayers, one way or another – not out of shareholder charity. All states with programs have some sort of transparent, although usually incomprehensibly confusing, means for cost recovery or lost revenue recovery.

Although the ACEEE paper did not say so per my read, there are three means to compensate/offset utilities for EE programs. ACEEE only discussed two of them in the paper linked above.

- First, there is the subject form of cost recovery, the lost revenue adjustment mechanism (LRAM). This model allows utilities to raise rates to get the revenue they would receive absent the program.

- Second, there is decoupling. If you use the terms sales and revenue interchangeably, you would have to stop that for decoupling. Revenue is independent of sales, in the short term.

- Third, not mentioned in the above linked report, is plain old program direct-cost recovery where customers are charged a flat rider on their energy bills. Those dollars are then channeled to the programs. I did confirm these are the three methods in another ACEEE publication.

- Fourth, performance bonuses or penalties for hitting goals.

The LRAM and decoupling are meant to remove the disincentive to deploy EE programs by maintaining revenue streams, essentially with higher prices.

Also, the ACEEE paper specifically states that the LRAM model “does not reimburse utilities for the cost of energy efficiency programs”. Utilities using LRAM recover their costs through the mechanism and usually, performance incentives.

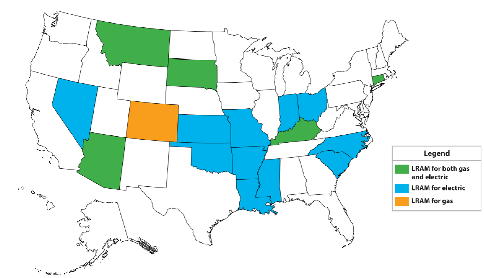

At this point, you may be thinking, “Hmm, I wonder how things work in my state.” Part of that answer is included in the map below, courtesy of ACEEE. The map highlights states that use LRAM.

Per my interpretation, the lost revenue adjustment is the trickiest to deploy equitably, for two reasons. The first is the dastardly counterfactual. Cost recovery depends on theoretical, hypothetical, pixy dust, Neverland (ok, I’m exaggerating a little) revenue, sans the program. Electric rates are adjusted upward to maintain revenue as electric sales fall in theory[1] due to programs. To address this, impact evaluation, including net-to-gross analysis, must be robust. Unfortunately, in my opinion, many people don’t seem to be that interested in the right answer in many jurisdictions. Maybe this is less of a problem in LRAM states.

Lost Revenue Adjustments

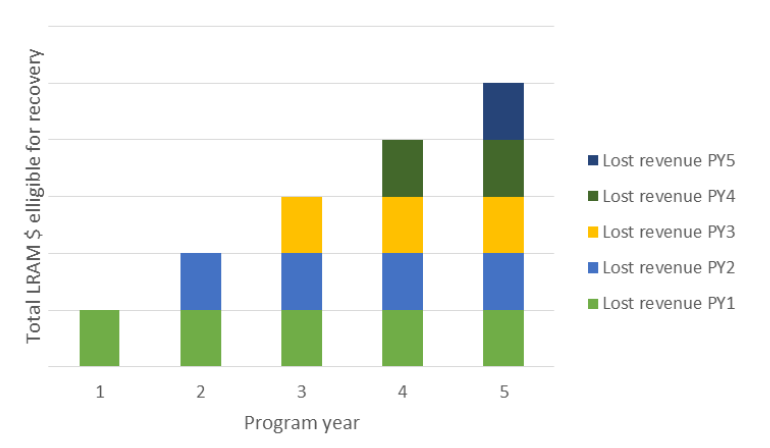

The second reason for lost revenue adjustment trickiness is that cost recovery charges can get out of whack between rate cases. ACEEE calls this effect “pancaking”, which to me sounds like flattening. I’d call it snowballing. This is shown in the chart. The LRAM cost recovery is literally a function of how frequent rate cases occur, for some states. When rate cases occur, the baseline is reset. In other states, it is reset after one year, or two years, and in one case, when the useful life of the measure expires.

Considering:

- Many people aren’t overly interested in the right answer. It could be they just don’t want to make the money available to do a decent job.

- The eternal quagmire of net-to-gross – what influence the program really had is impossible to determine with high confidence.

- Lost revenue recovery is a strong function of arbitrary adjustment timelines.

…the lost revenue mechanism is a mess to deploy.

Decoupling is much simpler, although not necessarily better. The revenue is prescribed regardless of sales, which depends on program effectiveness, the economy, weather, other things. Pixy dust not included.

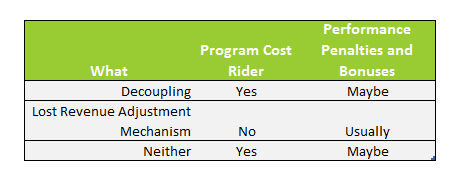

Cross checking with ACEEE’s State Energy Efficiency Scorecard, indicates that a patchwork of policies exist across the land, even within a state. One utility may do this and another may do that. To boil the options down, I created the table. Note that gas and electric policies may be different, and they may be different for the same gender (e.g., electric), different utility within a state.

Here is the thing that no one says: if sales are likely to increase, utilities should want LRAM, and if sales are expected to decrease, they want decoupling. Energy efficiency is only one itty bitty factor in the sales volume. The economy and other trending factors are far more substantial. Weather is a crapshoot.

If sales are trending down and I can lock my revenue in with decoupling, sign me up. There are true-ups over time, but cash flow rules. Utilities, like everyone else, want money now rather than later.

The LRAM only covers the effects of energy efficiency, not other major sales influencers. If the trend is increasing sales, and I can adjust my price for lost revenue on EE and apply it across the board, thank you, I’ll have another. The LRAM “does not make adjustments if the utility sells more energy than expected”, per ACEEE. Whoa!

By golly, looking at ACEEE’s data (Figures 13 and 14), LRAM states have more cost effective programs. They are spending their own money on programs (no direct program cost recovery), and they have the incentive described in the previous paragraph to demonstrate more savings, all else equal.

[1] Sales do fall but “in theory” concerns what sales would be without the program.