It seems like every time I visit my mother, at some point, maybe the night I arrive or the next morning over coffee, she starts dumping the local rubbish on me. So and so are “separated”. What’s her name is pregnant. Jimmy got busted for a DUI. Ronnie has cancer. I went to four funerals last week. And always something about my brothers, who as you may know run a large farming operation, are taking too much risk or can’t possibly afford this or that $300,000 piece of equipment. Being the anti-gossip and direct guy that I am, I ask, “Mom, why do I need to know these things?” and “You can’t do anything about it anyway, so why bother” and “I’m sure they know what they are doing, having been in the business for thirty years.” In summary, I don’t need or even want to know.

When I played little league and maybe even high school baseball, we had things like the 10 run rule and the point of that was to cut off the game and get on with something productive because the team getting hammered is never going to come back with any chance to win the game. It wasn’t for mercy. It wasn’t to protect the meek from getting clobbered 46-2, which everyone knows would happen if the game continued.

Reality can be unpleasant to painful or underwhelming and I only want to know about it if it affects me and especially if it’s something I can do something about.

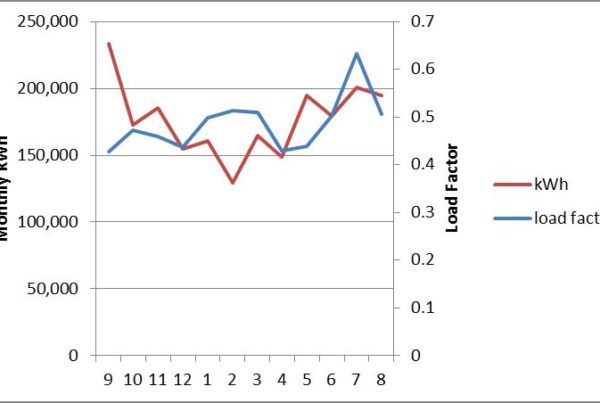

The majority of our energy efficiency work includes calculating energy savings and incentives for large commercial and industrial projects and evaluating all kinds (literally) of EE programs. Here we actually want as much information as we can get to do our jobs because hundreds of thousands of dollars can be in play and we like to get things right, especially when a lot of money is involved.

In some cases, it would be handy if the client accepted what “everything” means. It’s a little bit like describing what “no” means. One dictionary defines everything as, “every thing or particular of an aggregate or total; all”. And we write four memos regarding what “everything” means with respect to what we need. Everything. The reports, notes, manufacturer cut sheets, invoices, customer contact information, billing history, the maintenance guy’s favorite past time.

Other times we get a couple pages from a report, which is like grading an engineering exam while being provided with the question, and two equations the student wrote, and no answer. For example, a project includes the installation of a 500 horse power variable-speed compressor among several other existing compressors. The duty cycle for the new compressor is provided, but what was going on before the thing was installed? What other compressors are there now? Was it just installed to add more capacity? Answer: “never mind, here is the filtered information we want you to use”. “The consultant [providing the original study] knows what they are doing.” Ok. Let us see how terrifically brilliant they are as we review their work in its entirety. What’s to hide? Is this a game? Is that what this is, Lieutenant Caffey? Am I funny? Do I amuse you? Do I make you laugh?

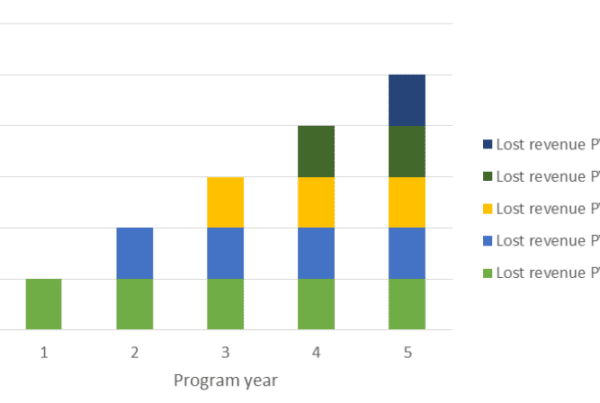

One of the most important purposes of program evaluations is to provide feedback to improve return on ratepayer investment from the program, an element of which is determining if savings are actually being achieved. I think everyone has seen sitcoms where the main characters messed something up or broke something and as a result they try to divert attention from it or put a happy face on a troll. What is the point in that when it comes to evaluation? I won’t speculate for the answer to that question. There are many possibilities.

Other times, the findings are plain as the nose on your face – like we metered lighting hours on 25 projects and they indicate an average annual burn time of 2,500 hours and not 4,300 assumed in the program’s deemed savings database. According to the implementer, the sample was faulty or it was not statistically significant.

We have to face the music at times when others review our calculations. If something is incorrect or uses inaccurate or non-representative data, or is for some reason generally a mess, we work with the reviewing engineers to make things right and if that means a savings adjustment, so be it.

The bottom line is, there are plenty of opportunities to capture real savings and we as an industry need to ensure we capture these savings rather than manufacturing savings by whatever the motive or reason.

In closing, to quote a guy I agree with 90% of the time, Mark Zweig, a consultant for consultants, “I never wanted to be one of those CONsultants who tells his clients what they want to hear and hopes he never gets fired. I am much more interested in being an INsultant who tells his clients what they need to hear.”

If a client doesn’t want to hear it, it is time for a new client.

Tidbits

Worthless EE tip of the week: disable your auto ice maker in your kitchen refrigerator and save 1% of your home’s electric bill. I believe there is a heater in the ice cube moulds to melt the ice so it can be flipped out. Whoopty doo. Yawn. If I understand it correctly, they say the ice cube makers pull an extra 84 kWh/year, which is about 10 W. A refrigerator only averages 50-60W running around the clock. Have your ice and eat it too.

In this article, we are informed that most consumers have no idea how much energy it takes to ship from factory to store. So I thought, what are the energy implications of buying local? How much transportation energy does this save? I like strawberries from Watsonville, CA. A truck hauls 60,000 lbs of strawberries 2,100 miles for roughly 350 gallons of diesel fuel. The diesel fuel it takes for my pound of strawberries would get me 0.17 miles in my thirty-mile-per gallon car. Worthless information? You be the judge.

Finally, there is this article on KFC’s sustainability efforts. The company rebranded itself because its former name sounded like a premature heart attack. Now it offers reserved parking for hybrid cars. First, people who drive hybrid cars would probably rather walk more, not less which leads me to the obvious second point, a Prius and a bucket of the Colonel’s best with a side order of stents is not a scene I can paint in my mind. I was going to stereotype and say KFC lots are full of SUVs, Buicks, Chevys, and minivans but I shall refrain and stick to the google street view facts from a Lakeville, MN (suburb of Twin Cities) store: 4 GM cars, 2 GM SUVs, 2 GM pickup trucks, 3 Chrysler minivans, 2 Chrysler cars, 1 Ford car, 1 Nissan SUV, 1 used defribulator, and zero hybrids.

Join the discussion One Comment