Last week, we briefly introduced an inquisitive concept: what is an incentive for, and who should get it? The rest of the post was consumed with a true story that could be called a merry-go-round of behavior that whipsawed a customer’s energy use over a period of several years.

Quantifying Behavior Barricades[1]

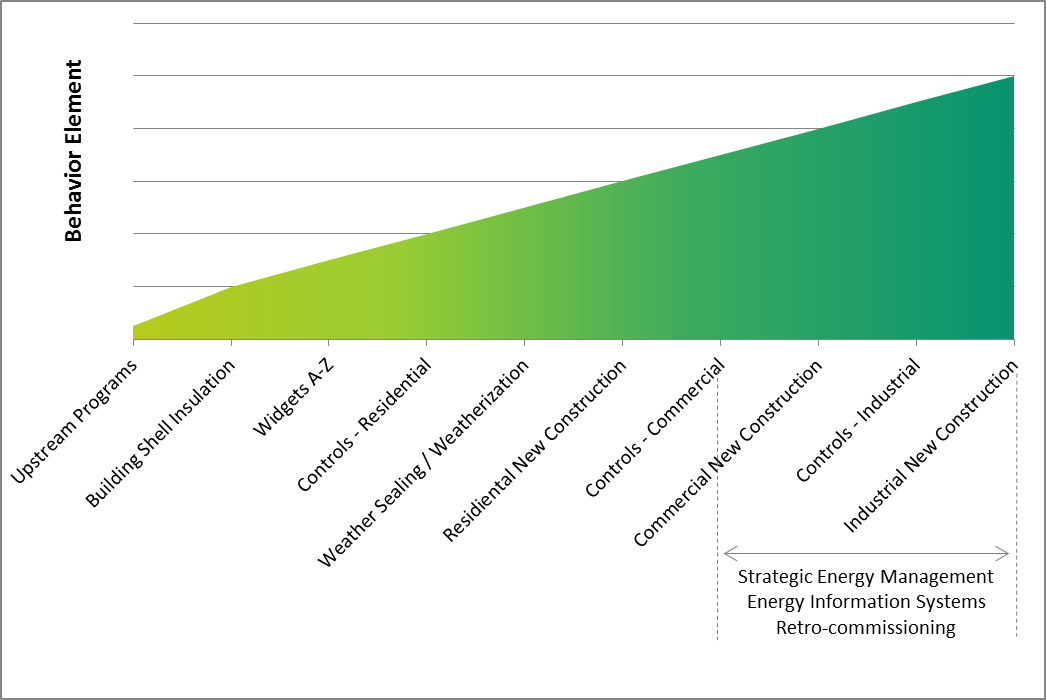

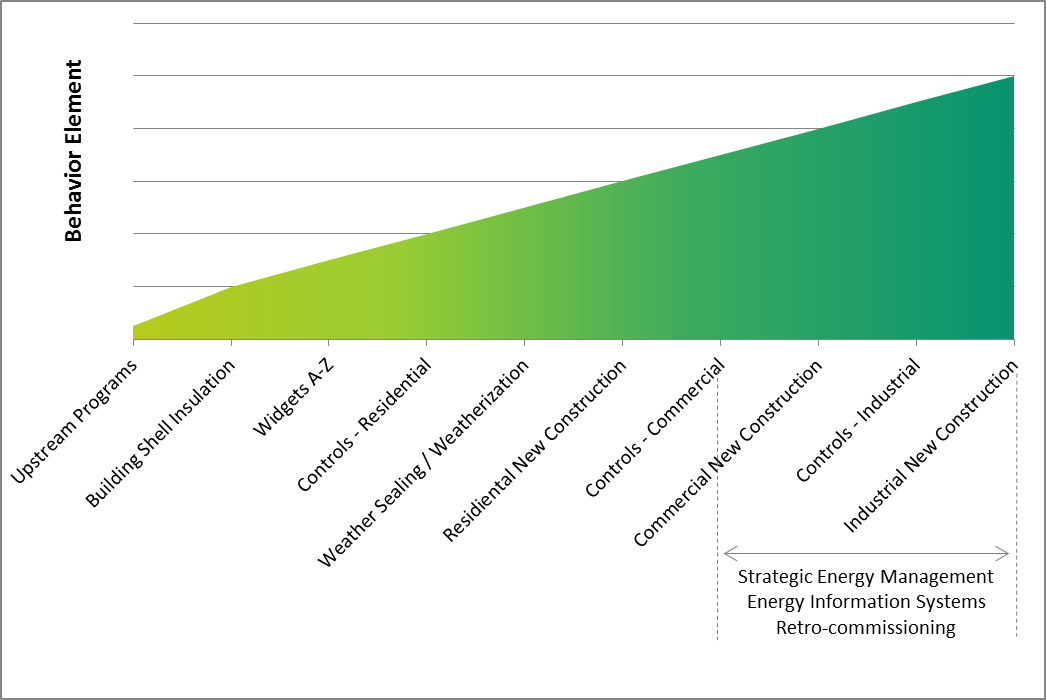

Every program has some level of behavior nudging. The chart illustrates my first shot for estimating the relative dimensions of behavior barricades that must be overcome for various buckets of programs.

The program type requiring the least behavior that I can think of is an upstream incentive program. For upstream programs, many/most participants don’t even know they are participating. At the high end are advanced programs that require vast knowledge (implementer), and overcoming stiff market actor resistance.

Behavior barricades come in a variety of flavors: customer, implementer, and market actor. On the low end of the curve, the barricades are more on the customer. On the high end, it shifts to implementers and market actors, but there can be a significant customer barricade as demonstrated last week.

Classifying Behavior Barricades

Behavior barricades exist not only by stakeholder group but by activity or class. A few examples:

Cost

Historically, cost has been viewed as the most substantial barrier. I used the word barrier rather than barricade because in many cases, if customers want something, they will find the money. For example, one of the coolest and most successful retro-commissioning projects we did was for a school district that received almost no cash incentive for anything – the investigation, analysis, engineering documents, or implementation. I attended the school board meetings and observed how they allocated funds from various sources. The project saved 40% on their bills, going on 10 years, with no degradation in impacts.

Customer Resistance

Cost is often a convenient excuse. Many years have passed, but at one time, I attempted with some success to sell energy efficiency projects. I didn’t know what I was doing, but I did know how the program worked. The program would finance everything for public facilities, including low/no interest loan for engineering assessment and analysis, and then funding implementation with a lease/loan that didn’t require referenda. After explaining all that, I many times got this answer: we don’t have any money. Palm of hand: meet forehead.

But also, as described last week, the primary stakeholders in a customer organization have to be on board. The decision maker and the facilities leader have to both be on board!

Knowledge

Implementer knowledge and expertise is something that is often erroneously taken for granted.

At one of the ACEEE Summer Studies for Buildings four – six years ago, I sat for a presentation that included reasons building simulations via computer modeling aren’t accurate. There can be many reasons including poorly performing controls, different equipment gets installed, hours of use is different than expected, and so on. But early on I was thinking – did it ever occur to you all that the modelers often don’t know what they are doing? User interfaces make computer simulators really easy to use, and dangerous, like a firearm.

A firearm is easy to use, but for an effective police officer or soldier, it requires a whole lotta training, discipline, and expertise. Get it? At least no one gets killed by simulator malpractice.

Market Actor Resistance

This is likely one of the most substantial barricades for programs we work in all the time – retro-commissioning, industrial new construction, and commercial new construction.

Consider retro-commissioning first. The controls contractor for any given project must be on-board, preferably with good attitude. I would say 80-90% of the time this is ok. Diplomacy, respect, and kindness go a long way, but that isn’t always enough.

For commercial new construction, there is resistance to change, which increases risk and cost (man-hours) for the designer/contractor. Two approaches work well for this. The first includes simply giving designers a menu of efficient choices to pick from and let them go. For example, you won’t beat a 93%-plus efficient furnace and a 16 SEER condensing unit. It has an extremely competitive first cost and operating cost, and virtually no one will object.

Larger facilities bring other issues. Even though energy codes permit obscenely complex, brute-force systems, these systems must go. They move huge volumes of air and water, and simultaneous heating and cooling is assured. I look forward to outcome-based programs – actual performance as opposed to pie-in-the-sky results from simulators that let these beasts fly under the radar.

Industrial new construction probably has even greater resistance. Contractors for these facilities have their preferred (only) way of doing things. If it works (and consumes 250% more energy than it should), don’t fix it.

A Solution

A solution for fixing these market actor barricades includes giving more of the incentive to the design and construction team. In the case of large C&I new construction, it may be most impactful to give half, or even more, of the incentive to these actors. If they don’t see a payout to take a chance, game over man.

[1] Barriers are obstacles to be negotiated. Barricades are…barricades.