Twenty-five years ago, I lived in the Northern Virginia suburbs of Washington: the distance from my condo apartment to work was four miles as the crow flies; a half hour as the car drives. Monthly parking fees were $100, so I biked. Today, in Wisconsin, these numbers are: practically free parking, eighteen miles, and still a half hour. I enjoy the drive, and apparently so do most of the rest of the US. This report by American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) provides interesting information on commuting practices in the US. What is this all about? Electric vehicle grid integration, or VGI.

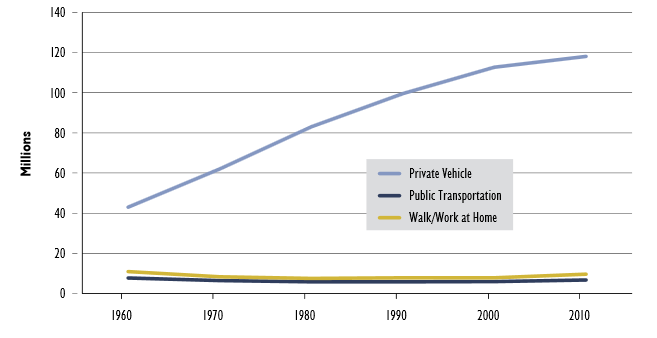

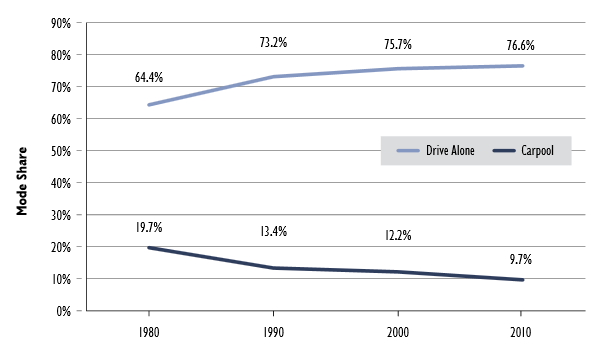

Although not part of this Rant, I can’t help but briefly point this out here: “Utility 2.0”, or the coming change of the customer-utility relationship, includes an expected stiff dose of consumer control over their lives. Touché. This is reflected in the graphical data shown above. More people are commuting alone at higher expense in exchange for freedom.

Led by California, dreamers are envisioning a future of electric vehicles constantly swapping electricity with the grid to maintain a steady supply/demand balance on the grid.

This report by the California Independent System Operator, CAISO, reads as though electric vehicles are like any other grid resource – that the only purpose of the resource is to support the grid.

If only that were true.

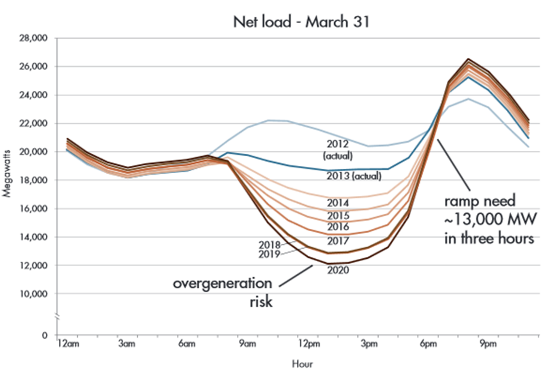

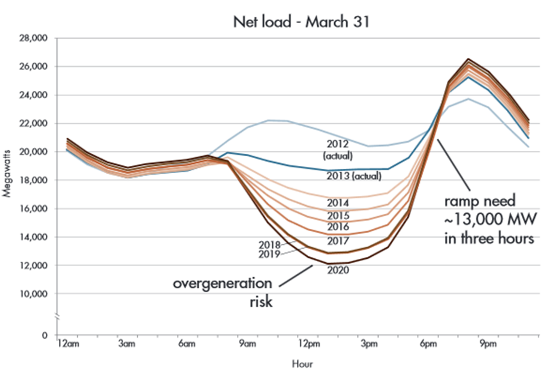

As demonstrated by AASHTO, most people use their cars for commuting to work. This is the proverbial swarm of flies in the ointment. At the same time in California (and I use California simply because they are heading down this road first), distributed generation via photovoltaic is growing extremely fast, as described in this post about the “utility death spiral” and the “duck curve”.

I’m reminded of an exchange from the great movie, Jaws. Quint: “Whadya have there – a portable shower or a monkey cage?” Hooper: “Anti-shark cage.” Quint: “Anti-shark cage. You go inside the cage. Cage goes in the water. You go in the water. The shark’s in the water. Our shark.”

Instead, “You go to work in the morning in your EV. Your PV panel generates power while you are at work. You drive home after work. Battery goes down. Sun goes down.” Perhaps I can coin a new term: the grave curve. A hole is being dug in the middle of the day, and at the same time the sundown peak gets higher – or in the case of EVs, they would get charged (with natural-gas power) while the driver sleeps.

This is the opposite of the so-called star alignment. The purpose of the electric vehicle is to transport people, and their stuff, to and fro. Generally, people are going to and fro during the day and during workdays, their vehicles are parked somewhere, and that somewhere has virtually no access to the grid.

Electric vehicles would need to be parked at home in their owners’ garages to integrate with the grid. Otherwise, more appropriate terms for interaction between the grid and EVs might be “accommodation” or “tolerance”. The grid accommodates or tolerates the use of EVs.

Anything is possible with mechanized/electrified equipment if enough money is spent. For instance, parking spaces can be decked out with charging equipment for EVs taking power off the grid while it is supplied by home PV in the region. However, the cost doesn’t stop at the charging station. The “pipes” for electricity feeding these parking areas would have to be upsized dramatically, at enormous cost.

Consider that according to the CAISO, a “fast” charging station charges at 50kW. Indeed, that is a lot of electrical power; roughly the demand of 20 homes at their simultaneous peaks.

Want to guess the rate of energy flow, converted to power in kW, delivered in gasoline energy at your local gasoline store? Five thousand kilowatts – enough to power a relatively inefficient 5 megawatt generator. Gasoline “charging” is 100x faster than a “fast” electric charging station.

A tanker truck delivering gasoline can carry roughly 90 MWh of energy to customer drivetrains, about one thousand 10-gallon fill-ups. That is enough for 250,000 miles of driving. Think about that – every tanker truck carries a lifetime supply of gasoline for one car. Meanwhile, that amount of delivered power would last your home roughly 7.5 years. Therefore, it is fair to say the average car, and the average home, burn energy (electricity only) at roughly the same rate over the long term – except the car is used only about 5% of the time, or 400 hours per year.

Comparatively speaking, the pipes (wires) delivering power to homes are tiny capillaries compared to the enormous capacity to deliver gasoline to consumers, inexpensively.

Smart engineers think in terms of bookends when considering what-if scenarios – what is the best and worst that can happen? A car’s lifetime supply of fuel can be delivered in minutes via gasoline, or 7.5 years over the grid. Enumerate that for a while.

Finally, someone who is making sense when looking at the affects of EV’s as a part of the elecric grid! EV’s are going to use more electricity not supplement the grid. The only way that would work is if EV owners stay home during the day and supplement the grid after they “charged up” over night. They are not going to supplement the grid while at work because they still have to drive home. As an electric cooperative, we are looking forward to the increase in kWh sales during off-peak night time hours.